New Justice of the Peace Judith Montreuil pledges to be fair and compassionate

January 18, 2018

Success doesn’t come without hard work.

Some, like Judith Montreuil, are required to work twice as hard to achieve their goals.

For nearly two years, the Haitian immigrant was a full-time employee and university student while raising three young children.

It didn’t matter that she managed just three hours sleep most days.

Montreuil just wanted the best for herself and her girls, which include twins. The divorcee knew she would see light at the end of the dark tunnel.

In front of proud family members, friends and colleagues, Montreuil was last week sworn in as a Justice of the Peace.

“I have shared the journey of my appointment with you to say that my standing here in this robe wearing this sash didn’t happen in a vacuum,” she pointed out. “It happened because I belong to a village that cares for me through thick, thin, the good, bad and the ugly. This village and all of its members have played a part in who I am today…I am honoured to be called to this bench, proud to now be one of its judiciary officers and humbled to be of service to the public. I promise to strive to preside in a manner that’s fair, compassionate, empathetic and dignified.”

While savouring the moment, she reflected on the journey.

As a Kids Help Phone counsellor and later clinical supervisor, Montreuil worked from 8 p.m. to 4 a.m. five days a week. After about an hour’s sleep, she was up preparing the kids for school before heading to the University of Toronto where she was enrolled in the Master’s of Social Work program.

At the end of a heavy daily workload on campus, Montreuil picked up her kids, went home and prepared dinner, put them to bed around 6.30 p.m. and then took a 45-minute nap before heading to work.

“I did that for almost two years,” she said. “The end goal was to be gainfully employed and available to my children. I was also demonstrating to my daughters that, ‘yes’, life can be tough, but only for a short time.”

Montreuil joined the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) in 2005, a month after graduating with her Master’s. Starting off with a two-month contract, she secured a permanent position a year later. After nine years as a frontline social worker, she was elevated to chief of social work & attendance.

Marcia Powers-Dunlop, the TDSB senior manager responsible for professional support services, hired Montreuil.

“She is so much well thought of at the board that people were in tears when they heard she was leaving,” she said. “In fact, some of them asked why I let her go. She has passion and compassion along with a wide variety of friends and skill sets.”

It was during her time at the TDSB that retired vice-principal Larry Maloney planted the Justice of the Peace seed.

“I remember him asking me what was my plan and I told him I loved what I was doing,” she recalled. “He said he didn’t see me being in that role forever and suggested I should consider becoming a Justice of the Peace. I didn’t know anything about what that job entailed.”

Retired four years ago, Maloney was convinced she was ideal for the role.

“As a volunteer in various programs in the Jane & Finch area, I could see that Judith had a genuine care for the young people she worked with,” he said. “That combined with her being very smart which is something she doesn’t flaunt and her ability to demonstrate sound judgement and make good decisions told me she would be an ideal candidate.”

Provincial court judge Donald McLeod also encouraged Montreuil to pursue the position after explaining what the job entailed.

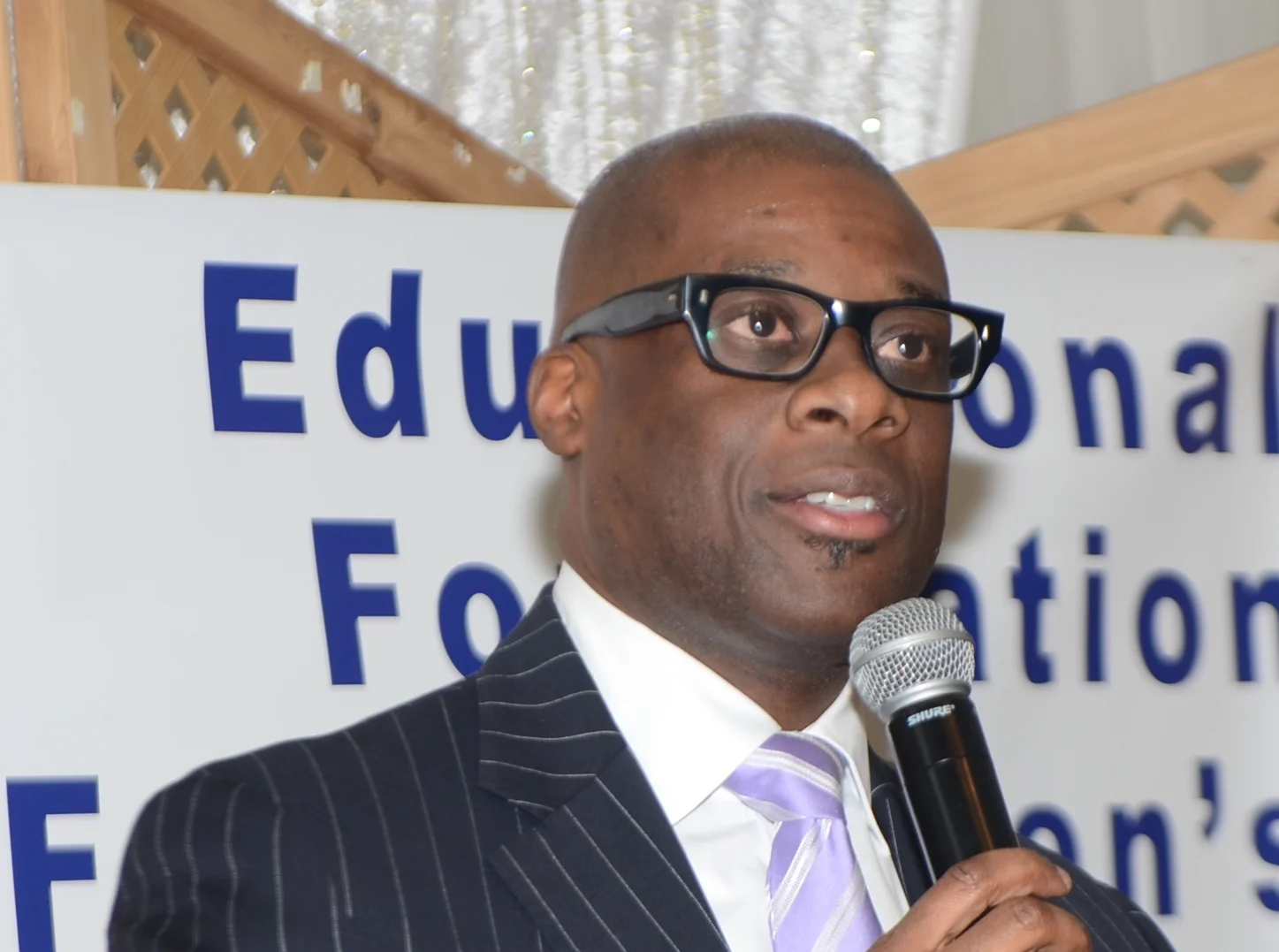

New JP Judith Montreuil flanked by Ainsworth Morgan (l) and Justice Donald McLeod

He put on her sash at the swearing in ceremony.

“Judith is very bright and has a good understating of the community which is a lens she could take when she’s adjudicating things in public,” McLeod said. “She is also personable which means that she isn’t separating herself from the community. What she’s saying is that I am willing to be here it with you, but it’s just that I am sitting in a different place which is the courtroom.”

TDSB public school principal Ainsworth Morgan met Montreuil about 10 years ago.

“She’s very intelligent, down-to-earth, community minded and proud of her heritage,” he said. “She’s going to do extremely well in her new role.”

Montreuil’s ascendancy to the mountain top was filled with potholes and obstacles.

Migrating to Canada at a young age in the early 1970, she spent nearly 15 years in Montreal before coming to Toronto.

“When I came here at age five, I could only speak creole,” she said. “That meant I had to learn French and later English. At around nine years old, my mom sent me to a Sunday school that was conducted in English to learn the language. It was challenging at first, but I was able to navigate the language within six months.”

Fed up with lack of opportunities in Montreal, Montreuil quit history studies at Concordia University and enrolled in York University’s philosophy program.

“I thought I was going to law school at the time,” she said. “But to be really honest, I didn’t know what I wanted to do.”

Completing her undergraduate degree in 1993, Montreuil was accepted into the university’s Master’s of Women Studies program. She left a few months later to take up a flight attendant position with Air Canada.

“Travelling and seeing the world was better than school and I enjoyed that for a year,” she said. “Nearing the end of the contract, I realised that wasn’t what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.”

Montreuil worked as a volunteer probation officer and sexual health counsellor before being hired by Kids Help Phone in 1996. Her first child was born two years later and the twins followed in 2001.

Justices of the Peace preside over virtually every judicial interim release hearings in the province and the majority of criminal remand courts.

Assigned to Toronto, Montreuil is confident that she can be effective judicial officer.

As a social worker, she worked extensively with children and families in the field of mental health. Her practice interests are rooted in the areas of child/parent conflict resolution, student wellness, parenting strategies, family mediation and student and parent engagement with respect to the educational system.

Montreuil is acutely aware of issues faced by marginalized populations and the ways in which these issues converge to create and sustain patterns of inequality.

“I have a really solid understanding of closed systems,” the former Sheridan College sessional professor, York University faculty adviser and Boost Child & Youth Advocacy trainer said. “One of the observations I have made is that when someone gets caught in the crosshairs of the child welfare, education and judicial systems, it is the holy trinity of not having a way out. These systems endeavour often to bolt a person down to their experiences and resistance. As the individuals who work in the system, it’s up to us to understand how to we facilitate access and understanding and how do we promote equity in these very tight constricted systems that really, at heart, have the notion of punishment moreso than rehabilitation or the ability to lift people.

“In this role, I will be the person that facilitates people’s understanding of what it is they are involved in. I will hold the system accountable. I am asking the officers that are there to represent the public to do so in a way that’s compassionate, transparent and fair. I don’t want to just accept that is what it is. I want people to understand what it is and I want them to get a sense of, ‘ok, it may be what it is’, but I can find power in this by asking the right questions. If I can’t do that, let me find someone who can do that on my behalf. I want to promote that because it’s too easy to say this is the way things are.”

When thinking about whom she could dedicate the Justice of the Peace appointment to, the person she felt deserved that honour the most was her maternal grandmother, Amencie Nostrum, who died in Haiti 55 years ago.

“She passed away when my mother (she has three Master’s degrees and resides in Montreal) was in her mid-teens,” said Montreuil. “But what I have been told about this absolutely amazing woman is that she was a visionary who was born well ahead of her time. At 4’11”, my grandmother saw well beyond the shores of her island nation and envisioned a future for her children that knew no boundaries and that had no limits. And in her short life, she managed to pass on to my mother and her brothers her work ethic, her love for adventure, her love for learning and her love for others. I am eternally grateful for her spirit and I am proud to stand on her shoulders and to be her grand-daughter.”

Haiti, the world’s first Black republic and the first country in the Western hemisphere to abolish slavery, remains close to Montreuil’s heart even though she hasn’t been back in almost two decades.

“Haiti is where my heart will live and die, but it’s a country that often doesn’t know what to make of me because I am from the diaspora and I am a transplant,” she said. “There’s a real sense of despair that comes when her children come home because the question then becomes, ‘what have you done for us lately?’ It is such a complex web of circumstances that it’s impossible for you take it apart when you are returning home, but really as a tourist at so many different levels. At the end of the day, the nation doesn’t even know how to receive you back.”