Judge says kids not doing as well as their immigrant parents

May 11, 2017

Blacks are better educated, far more involved in the labour market and economically richer than they have ever been before.

That’s the good news.

The bad news is that a large percentage of Black youths are dropping out of high school and African-Canadians account for nearly 10 per cent of the prisoner population even though Blacks make up just three per cent of Canada’s inhabitants.

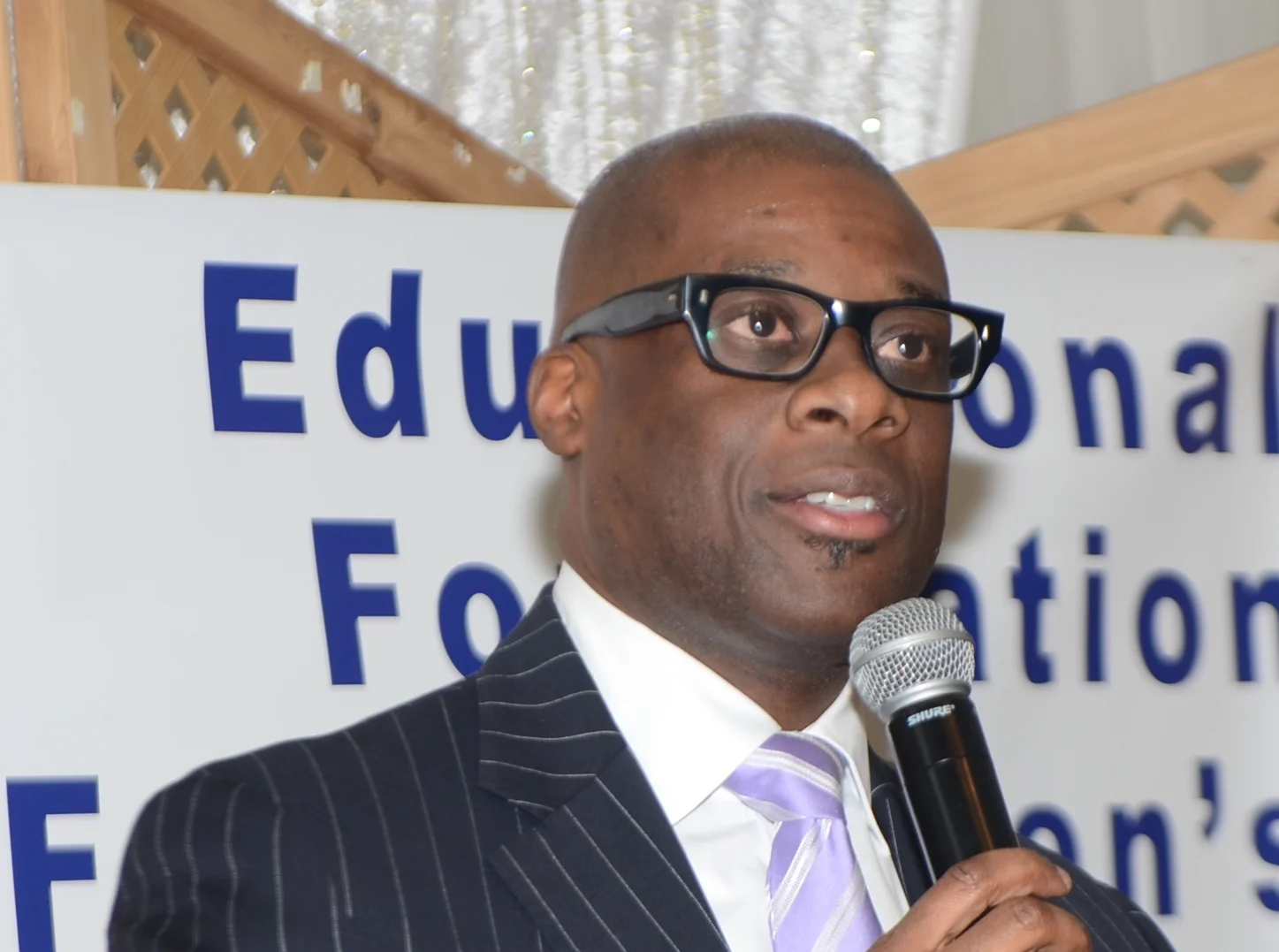

In presenting the troubling statistics during his keynote presentation at the Wilson Project seventh annual fundraiser in Durham, Justice Donald McLeod said the data shows that second generation Canadians are not achieving the same high levels of education as their immigrant parents.

He said immediate and decisive community action is needed to buck the disturbing trend.

“As a Black community, we must move back to an understanding that the benchmark is excellence,” he pointed out. “It is incumbent upon us as parents, you as students and we as a collective community that we no longer pay lip service to the notion of good, better and best. At this point in time, we are losing the battle because we haven’t allowed our children to do what made us successful.

“We have relaxed, we have lowered our standards, we have spent more time getting things that we can afford and we are far too busy keeping up our lifestyles and not concentrating on our children…I believe that if you don’t live struggle in your lives, you will not be ambitious.”

As a young child, McLeod didn’t have it easy.

He grew up in a cockroach infested Regent Park apartment and was forced to sleep with the oven door open in winter to stay warm.

“That was my reality and the kind of one you have that makes you say I want to get out of here,” McLeod said. “You often hear people say that individuals living in these neighbourhoods are at-risk. This is not something that I take too kindly to because I don’t believe people that aren’t from my neighbourhood are in any position to define me. Sometimes we allow that to happen and then we believe whatever the definition is that they place on us. I speak against that. For those of us who grew up in some of these neighbourhoods and even those that didn’t, the reason why I think we are getting worse and worse is that we are getting farther and farther away from struggle.”

Two years ago, McLeod’s son – Caleb -- broke his iPad and was expecting his father to buy a new one.

That hasn’t happened even though the provincial court judge could afford it.

“Because we have enough resources, we can go to the store and spend $300 or whatever it costs to buy Johnny a new iPad,” he noted. “When you do that, he is so happy that he looks at it and admires it. But he didn’t have to struggle. My son’s iPad is still broke because he has to understand that my iPad still works because I didn’t drop it anywhere.

“…Our children believe that what they have is because of them. So when they decide they are not going to apply for post-secondary education and when they say to themselves they are to going to do the best they can, it is because as far as they are concerned, when they come home they can get a new iPad. We can’t keep giving the next generation the tools that are going to be adverse to them. We, as a community, must recognize that we have to start to give our kids just enough and not more than enough.”

An accomplished litigator with a very keen interest in community and social justice issues, McLeod can identify with the many Black male students who are struggling in high school.

Raised in public housing without a father, he failed every subject in Grade Four, including gym and took general courses in Grade 10. The only reason he ended up at McMaster University was because the name sounded good.

McLeod, who as a lawyer successfully argued the R v Golden case in the Supreme Court of Canada in 1999 that addressed the constitutionality of police strip searches and the landmark 2009 R v Douse case that revolutionized the traditionally used racial vetting process that now takes into consideration non-conscious racism, is now doing his part to uplift and empower young Black males.

He founded and chairs 100 Strong, an initiative to fund a summer school program for 12- and 13-year-old Black boys and co-chairs Stand-up which is a mentorship program for Grade Seven and Eight boys, the majority of whom reside in designated priority neighbourhoods.

In addition, McLeod makes frequent motivation speeches and hosts Black Robes, a professional development project aimed at mentoring new lawyers and law students of African-Canadian descent.

Kenroy Wilson started the Wilson Project in 2010 to raise scholarship funds for young people.

At his lowest point after his father, Ralph Wilson, was murdered in South Carolina 17 years ago, Wilson, received support from teachers.

“I loved cars and putting things together so one of my teachers suggested I could try doing body work and painting cars in cool colours or become a mechanic,” said Wilson.

Kenroy Wilson

He did co-op placements and worked part-time at Pickering’s Formula Ford and then Honda which hired the youth full-time and enrolled him in Centennial College’s Acura/Honda 32-week automotive service technician apprenticeship program, where he was exposed to classroom training and work experience with an Acura/Honda employer.

Graduating as a licensed technician, Wilson spent nearly six years with Honda before leaving 11 years ago to set up his own business, Ken Co’s Car Care Inc.

Remembering the pivotal role teachers played in rescuing him, Wilson is giving back to his community in a big way. He mentors young Black boys who are distracted, frustrated and have been in trouble with the law and provides job training opportunities at his mechanic shop.

When Mary Lawand, who taught Wilson from Grades One through Eight at Frenchman’s Bay Public School and played a key role in helping him assimilate in Canada after migrating from Jamaica 25 years ago, succumbed to a brain tumor in January 2016, he established a scholarship in her name.

Administered by Centennial College, a full-time student enrolled in a Ministry-approved post-secondary program who has overcome challenges is awarded $1,000 annually

The married father also supports two Centennial College-administered bursaries that bear his deceased father’s name. They are presented annually to second-year students excelling in the automotive technician program.