Peter Rosenthal was a human rights protector

May 31, 2024

In the late 1970s, deceased civil rights lawyer Charles ‘Charlie’ Roach and his law partner Michael Smith, along with community activist Owen Leach, drove to a Windsor jail to meet Chrysler Canada autoworker Clarence Talbot who was accused of murdering union boss Charles Brooks over an alleged grievance in January 1977.

Fearing he might not get fair representation, Roach and Smith went there to advocate for the amateur boxer who died in 2003.

Before entering the facility where Talbot was held, they ran into local attorney Harvey Strosberg who they did not know was representing the accused who was Black.

When the judge determined that he would not get a fair trial in Windsor, it was moved to Toronto and Strosberg suggested Edward Greenspan as his replacement. Strosberg also took Roach and Smith before the Law Society of Upper Canada, accusing them of attempting to poach his client.

They hired Peter Rosenthal, then a Math professor and non-lawyer, to defend them.

“It was a very serious matter because my father was facing severe legal sanctions if he was found guilty,” recalled Roach’s daughter, Kikeola Roach. “The case drew a lot of attention with large numbers of people protesting outside the Law Society building. For as much that was on the line, for my father to choose someone who was not a lawyer to go before the Law Society said a lot.

“Something that was underlying there was an alliance about deep-seated shared values of challenging the status quo by being fearless in the face of establishment pressure. Led by his sense of justice and skills, Peter was not intimidated and just took it on.”

The charges were dismissed.

Rosenthal, who went on to become a lawyer and the Black Action Defence Committee’s (BADC) main legal representative, passed away on May 25. He was 82.

Ontario’s Chief Justice Michael Tulloch learned about Rosenthal while he was in law school in the 1980s.

“I was fascinated by the fact that here was a Math Professor who was working voluntarily with Charles Roach and Michael Smith on legal cases, representing primarily Black men in inquest hearings,” the former Canadian Association of Black Lawyers President said. “Peter was not a lawyer at the time, but he had a passion for the Black community even though he was not from the community. Throughout his legal career, he was a beacon of hope for many. His tireless advocacy and profound empathy in court, his strategic acumen and his passionate defence of human rights earned him a reputation as a legal icon within the justice system.”

Tulloch, who is also the Court of Appeal for Ontario President, noted that Rosenthal’s contributions extended beyond his courtroom victories.

“He was a mentor, teacher and an inspiration to countless individuals who sought to follow in his footsteps,” he added. “Hs legacy is reflected in the lives he touched, the injustices he fought against and the enduring impact of his work on the Canadian legal landscape.”

The product of a social activist mother who fought against nuclear armament and racism, Rosenthal took part in the Woolworth lunch-counter sit-ins in 1960 in New York where he was born and raised before coming to Canada in 1967 to take up a position as an Assistant Maths Professor at U of T.

Though a brilliant Mathematician, ‘the red diaper baby’ was quick to act when he spotted an injustice.

A few months after his arrival in Canada, Rosenthal was arrested in downtown Toronto while delivering a speech, protesting the United States’ role in the Vietnam War.

Charged with obstructing a police officer and inciting a disturbance, he fired his young lawyer and represented himself at the trial where he was convicted of a charge that was later overturned on appeal.

Rosenthal also represented 26 others who were charged in the demonstration outside the United States consulate.

Becoming very interested in the law, he volunteered as a paralegal representing friends and activists. When the Law Society threatened him for practicing without a license, he hired Roach as his legal representative. The Law Society abandoned its action after Roach moved a motion to move the disciplinary proceedings to court.

Encouraged by Roach to go to law school, he was admitted to the University of Toronto in 1988 at age 47.

Rosenthal then articled with Roach before being called to the Ontario Bar in 1992.

In addition to acting as counsel for BADC, he represented Black and visible minority families in several high-profile inquests. The cases include Ian Coley, Raymond Lawrence, Michael Eligon, Henry Musaka and Faraz Suleman who were shot by police.

“Peter was an unusual character in that he was someone who was very consistent over a long period of time of taking up many cases that hit the Black community at its core,” Roach said. “He was one of the lawyers that probably did more inquests trying to seek systemic changes to the policing system than any other lawyer in this country. He was solid in his beliefs and principles, living those out through his work. He abhorred any abuse of power and was interested in making systemic change.”

Rosenthal, who did a lot of pro bono work, worked with Charles Roach from 1975 to 2012 when the Trinidadian-born lawyer and activist died.

To honour Roach, he led a successful campaign for a public lane in the city to be named after his close friend.

The laneway, close to where Roach’s law office once stood, was unveiled in July 2018.

“It was very easy to get support for this,” Rosenthal pointed out at the unveiling ceremony. “Charlie contributed to fighting racism and other injustices and was fantastic in that respect. He always stood his ground and was courageous about doing so.”

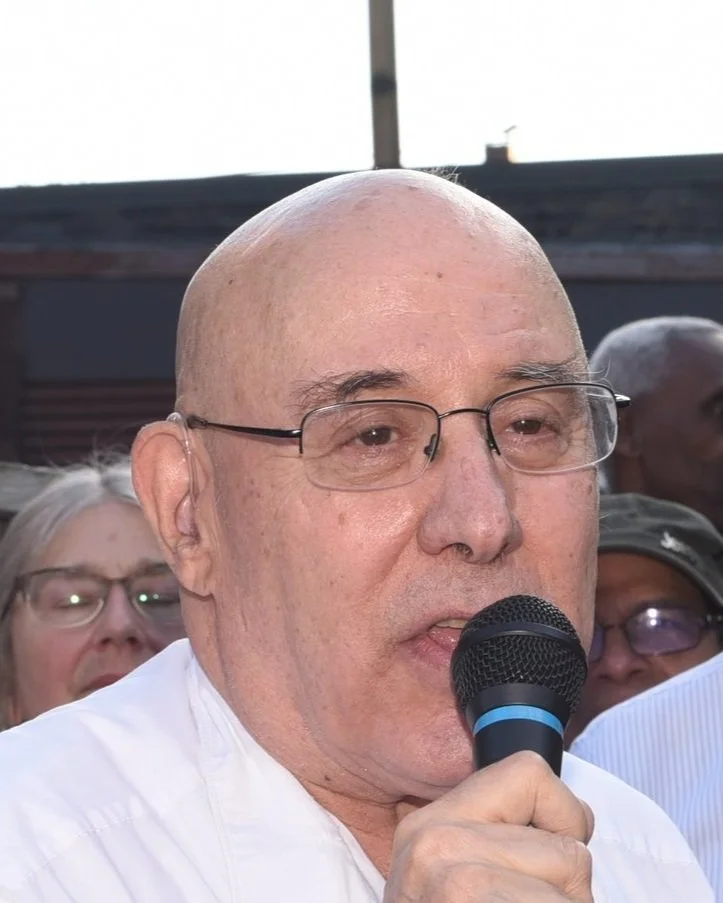

Peter Rosenthal speaking at the Charles Roach Laneway unveiling in 2018 (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

The U of T Professor Emeritus was also part of a group that launched a petition requesting the Canadian Cabinet direct the Minister of Citizenship, Immigration & Multiculturalism to award Roach citizenship without him having to take the oath.

A permanent Canadian resident, Roach vehemently refused to pledge allegiance to the Queen which is a requirement for all citizenship candidates over the age of 14.

He lost out on an opportunity to become an Ontario court Judge because it required the oath which he opposed. He also did not possess a Canadian passport and was unable to vote despite living here for 57 years.

In September 2013, a Judge ruled that taking the Oath is not to the Queen as a person, but as a symbol of Canada.

Rosenthal and his legal team, that included Selwyn Pieters, appealed the decision to the Ontario Court of Appeal that dismissed it.

Licensed to practice in Ontario, Guyana and Trinidad & Tobago, Pieters said Rosenthal mentored him from the time he entered law school until his retirement.

“As a first year law student, I worked with him on the Allan Garden Cases,” he pointed out. “As a first year lawyer, we did Freeman-Maloy v Marsden, Stevens v Conservative Party of Canada and others. I thank Peter for the mentorship and the meetings in the war-room that he led which were something for the books. A lot of the learnings remain.”

In addition to Roach, Rosenthal also represented late activist Dudley Laws who was charged with smuggling illegal immigrants across the border into the United States in 1991.

Convicted at trial, the Court of Appeal ordered another trial, but the Crown stayed the charges.

“When Peter made the decision to participate in helping to construct positive Black imagery, Laws and Roach were at the centre of that,” said long-time BADC member Dari Meade. “Impressed by his consciousness, Charlie recruited him and, in so doing, showed us how we can widen when we interact with other communities, particularly the White Jewish community. He was one of those guys that centred himself in humanity and dignity.”

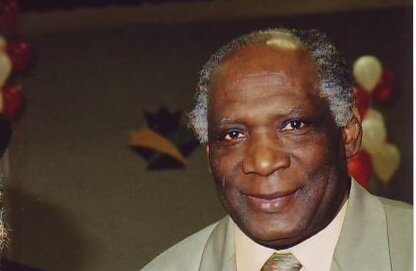

Peter Rosenthal along with Nzinga Walker (l), Denham Jolly, Dudley Laws and Charles Roach at BADC’s fourth annual dinner in October 2000 where Akua Benjamin was honoured for her advocacy work (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

Social Work educator and community activist Dr. Akua Benjamin said Rosenthal was the Black community legal backbone.

“That was particularly the case when it comes to BADC,” she said. “There was no other lawyer that we could call at a moment’s notice when we had an issue. He stayed through thick and thin. You could always rely on him.”

Rosenthal selflessness caught the attention of retired teacher and community organizer Lennox Farrell.

“He was also someone who kept his word and took on community work in the way some take on their profession,” he added.

Rosenthal is survived by his wife, Carol Kitai, and five children.