UWI Luminary honour for renowned sculptor Basil Watson

May 30, 2022

With his public sculptures and monuments displayed globally, renowned figurative artist Basil Watson would welcome a call to design historic markers in Canada of Jamaican or Caribbean immigrants who have left an indelible imprint in their adopted homeland.

He created the Miss Lou (Louise Bennett-Coverley) statue that was unveiled in rural Gordon Town, Jamaica, in September 2018 to mark her 99th birthday.

The Miss Lou statue in Gordon Town, Jamaica (Photo contributed by Basil Watson)

The cultural ambassador spent the last 20 years of her life in Canada before passing away in 2006 at age 86.

The Miss Lou Archive is housed at McMaster University, a cultural room at Harbourfront Centre bears her name and York University bestowed her with an honourary degree in 1998.

Watson, who has a soft spot for the late poet and folklorist because she was an artist, is open to the opportunity of creating a replica of the Miss Lou sculpture in Canada.

“Miss Lou was highly revered in her adopted country and I think it would be tremendous to have something like that here,” he said. “On top of that, there are Caribbean nationals in Canada who excelled and deserve to be memorialized through art.”

As a University of the West Indies (UWI) Toronto Benefit Gala Luminary Award recipient, Watson will be in Toronto on June 25 to receive the honour.

His previous two visits to Canada were as a 10-year-old and a participant in a karate tournament a few years later.

“To be recognized by a larger than life leading light Caribbean academic institution means a lot to me because it’s so much more meaningful when that honour comes from my people,” the 64-year-old artist, who has lived in Atlanta since 2002, said. “I always saw UWI as a very special place for the development of Caribbean people.”

Having a father who was one of Jamaica’s foremost artists made it easy for him to choose a career path at an early age.

The late Barrington Watson (l) was the recipient of an Award of Excellence presented by the Kingston College Old Boys Association (Toronto chapter) in November 1998. Then president Norman Wallace made the presentation (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

Barrington Watson, who in 1998 was honoured with an Award of Excellence by the Kingston College Old Boys’ Association (Toronto chapter), passed away in January 2016 at age 85.

“I was told that when he brought home his paintings, I would stand in front them and stare,” he recounted. “His vision to see his life as an artist impressed me. If he could do it, so could I.”

Besides his dad, Watson looked up to late Frenchman Auguste Rodin who is considered the founder of modern sculpture.

“I learnt of him through my father who spoke glowingly of this man pushing sculpture beyond what Michelangelo had done,” the 6th degree Black belt holder and karate teacher said.

‘Naked Came I’, a 1963 bestselling novel based on Rodin’s life, was one of Barrington Watson’s prized possessions.

“I read that book at a fairly young age and started to research him,” said Watson who credits his mother, Gloria Watson, with teaching him empathy and the power of observation and sensitivity. “That’s where my fascination for him grew and the way in which he approached the human figure. What he did combined with my dad’s work heavily influenced the direction of my work.”

Seeking an institution that provides an artistic education, he attended the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts.

Respected painter Alexander Cooper, who died in March 2020, successfully encouraged Watson -- who he taught art at Kingston College -- to participate in his figure drawing classes at Edna Manley that was formerly the Jamaica School of Art & Crafts. (Barrington Watson was the institution’s first Director in 1962.)

Christopher Gonzalez – who is best known for the 2.7-metre statue of Bob Marley that is on display in Ocho Rios – was Watson’s sculpture tutor in his first two years at Edna Manley.

“Through his passion for sculpting and life, he influenced me to go into sculpture as my final medium,” he said.

While at Edna Manley, Watson was also exposed to the teachings of George Rodney, one of the pioneers of the modern Jamaican art movement, ceramicist and sculpture Gene Pearson and painter Hope Brooks.

“These Jamaican luminaries inspired me in a major way,” he pointed out. “The enthusiasm for the arts was extremely high as the transition was taking place from the Jamaica School of Art & Crafts to Edna Manley.”

Prince Harry congratulates Basil Watson at ‘The Rings of Life’ unveiling in 2012 (Photo contributed by Basil Watson)

At age 44 and well established in Jamaica, Watson migrated to the United States to expand his career.

“I had already done a dozen or more public sculptures,” he noted. “But I was finding it difficult to make it on the international stage. That was around the time that social media was emerging and I was seeking a bigger platform. Living on an island also meant packaging and shipping. For my career, it thought the best thing for me would be to move to North America.”

With the art establishment falling in love with abstraction in the mid-20th century, figurative art became almost archaic.

The energy, vigor and emotive quality of the human figure intrigues Watson whose older brother Raymond is also a sculpture. It has also sustained and anchored his work.

“When I started in the 1970s, the human figure was somewhat passé,” he said. “More abstractionism and expressionism were trending, but I had a passion for the figure which my father told me would return. There was a lot of experimentation in Jamaica at the time, but I stuck with the figure. Art has moved to a point where we are much more inclusive. It is no longer about one trend or the other. We can all co-exist speaking one language.”

Three days before the Toronto honour, Watson’s first public artwork in England -- which is a tribute to the Windrush Generation – will be unveiled.

Commissioned by the British Government, the Windrush Generation statue will be unveiled on June 22 (Photo contributed by Basil Watson)

He beat out three artists of Caribbean heritage for the right to design the 12-foot National Windrush Monument at London’s Waterloo Station.

Watson used figures of a man, woman and child representing the family climbing a pile of suitcases filled with their possessions.

This creation is very personal as his parents met on a boat while travelling from Jamaica to England in the early 1950s. Though born in Jamaica, he spent about four years in England before the family re-migrated in 1962.

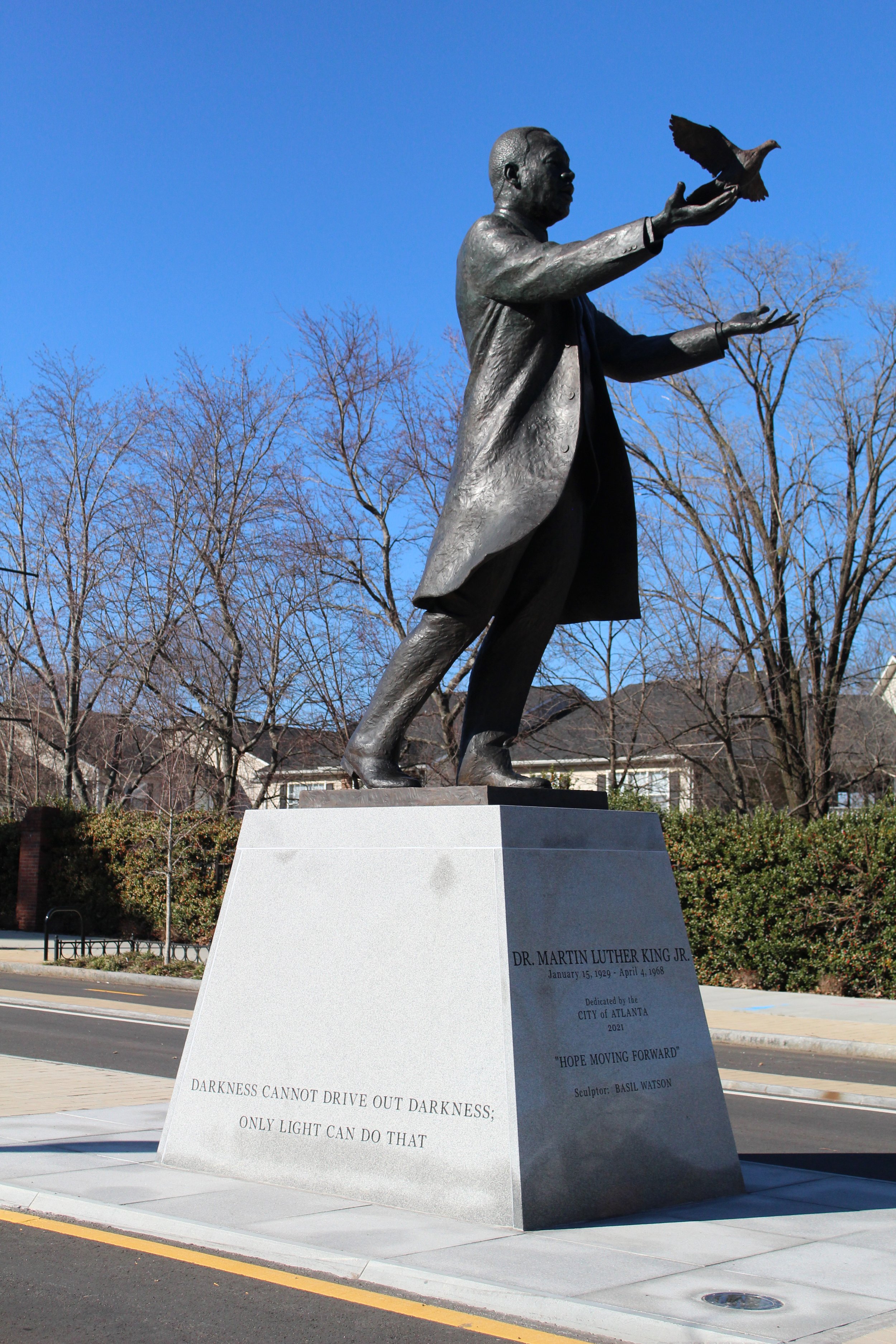

Watson also designed the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. sculpture that was unveiled in Atlanta in January 2021. Titled ‘Hope Moving Forward’, it took two years to complete and features King releasing a dove.

The Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. statue in Atlanta (Photo contributed by Basil Watson)

“Martin Luther King was always a hero of mine, so to get the opportunity to sculpt him in Atlanta where I live was an amazing honour,” said Watson who was chosen from a pool of 80 talented artists and whose father did a portrait of MLK when he lectured at Spelman College in the late 1960s. “Though I live in the suburbs, I drive by the statue on some occasions just to pinch myself to make sure I wasn’t dreaming.”

The Usain Bolt statue outside Jamaica’s National Stadium (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

Sculptures of Jamaican track and field stars Usain Bolt, Shelley-Ann Fraser-Pryce, Asafa Powell, Veronica Campbell-Brown, Merlene Ottey, Arthur Wint and Herb McKenley designed by Watson, stand outside Jamaica’s National Stadium.

Merlene Ottey’s statue stands outside Jamaica’s National Stadium (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

In 1961, late Jamaican sculptor Alvin Marriott’s creation ‘The Runner’ was unveiled at the National Stadium to celebrate the achievements of McKenley, Les Laing, Arthur Wint and George Rhoden.

Wint won Jamaica’s first Olympic gold medal at the 1948 London Games in the 400-metre final. He also picked up a silver medal in the 800-metre event at the same Games and again in 1952 in Helsinki where he teamed up with the other three athletes to finish second in the 4 x 400-metre final.

“I was fascinated by the fact that my parents knew these heroes,” Watson, who was recognized with the Jamaica Order of Distinction (Commander Class) in 2016, said. “I remember looking at that sculpture and thinking how cool it would be for me to have a sculpture in the public domain. I dreamed about having just one and now I have seven. That is beyond belief.”

The statue of Herb McKenley (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

He also created ‘The Netballer’ bronze resin commemorating Jamaica hosting the 2003 World Netball championship, a bronze statue, ‘Balance’, marking the 100th anniversary of Doctor’s Cave Bathing Club in Montego Bay and the George Headley bonded bronze sculpture at Sabina Park.

Watson is completing a life-size bronze statue of Bolt to be mounted at the Ansin Sports Complex in Miramar, Florida later this year. He has also being commissioned by the City of Eatonton in Georgia to sculpt the image of original Tuskegee Airman and Congressional Medal of Honour recipient Hiram Little who died five years ago at age 97.

Watson and his wife of 43 years, Donna, have three children.