Al Mercury's life was dedicated to community service

May 6, 2020

Far too often not acknowledged and taken for granted are community stalwarts who paved the way and on whose shoulders many stand.

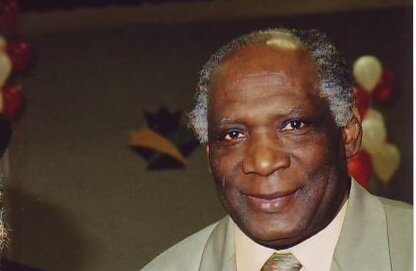

One such giant who made a mark was Albert ‘Al’ Mercury who died 22 years ago on April 1, the same day that another revered activist – Ed Clarke – was laid to rest.

Leading with a dignified style, he dedicated his life to helping people of all classes and races.

“My father was a connector who brought people together,” said Lee Ann Mercury, the eldest of three siblings. “He was also interested in extending those connections. At his funeral, there were people I knew in different ways who looked at each other and asked, ‘Why are you here’? They didn’t know they both knew him. I heard that from a number of people and was shocked.”

During a lifetime of community work, Mercury served on many boards, commissions and organizations. He however derived the most satisfaction from his work as a Lion.

“Where else, he would say, can you mobilize a community to do something for others less fortunate than yourself without any hope of any monetary return or personal publicity,” said Art Kirkwood who met his best friend in the late 1930s in Grade Three at Orde Street Public School. “He took the Lions motto, ‘We Serve’, very seriously. Serving meant to him exposing racism in all its forms and reaching out to the disadvantaged. It also meant serving in any other way to make this city and country a better place.”

Al Mercury (back row centre with glasses) and fellow Lions members including Robert Payne (sitting centre) Leslie Hutchinson (right) and the late Howard Matthews (l)

Invited by a friend in 1969 to attend the Toronto Gateway Lions Club charter night, Mercury ascended to the club presidency the following year and within four years became the province’s first Black District Governor with responsibility for 41 clubs in the city.

“That was a very big deal for my dad,” said Mercury’s daughter. “He became a Lion because he liked what the service organization stood for. He also realized there weren’t a lot of people that looked like him who were into Lionism.”

Lee Ann Mercury with her godfather Art Kirkwood (c) and Arthur Downes at the funeral

The void led Mercury to start the Toronto Bathurst Lions Club and, with historian and educator Dr. Sheldon Taylor, the Toronto Onyx Lions Club.

“There was a Lions club in the city for Italians at the time and I think that was the genesis for him starting the Bathurst Club,” his daughter pointed out. “He knew a lot of people that were born here and the members of that Italian Club were also born in this city. What he recognized was that under the banner of Lionism which is a global organization, there was an opportunity for influence by having that global banner behind you. He was pretty excited about that and he used that model to help start other clubs in other communities.”

Born in 1932 to Rev. George and Gladys Mercury who were immigrants from St. Vincent & the Grenadines and Jamaica respectively, Mercury completed high school at Harbord Collegiate Institute and graduated with an honours degree in English from the University of Toronto’s Victoria College.

Paying for his university education with the money earned working as a Toronto District School Board janitor, he taught English at North York high schools, worked for 7-Eleven choosing managers for its outlets and started a personnel agency.

With an interest in race relations, Mercury co-chaired the North York Race & Ethnic Committee for 13 years until 1992 and was the executive secretary of the National Black Coalition of Canada created in 1969 a few months after Canada’s largest student occupation at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia University).

He also served on the Toronto Police Service Complaints Board, the federal and provincial Parole Boards, the Urban Alliance on Race Relations executive, the Metro Toronto Housing Company Ltd. and the Metro Toronto Housing Authority and was a John Howard Society member.

In 1993, Mercury was part of a group of community leaders that failed in a bid to create an umbrella Black Think Tank to share information and arrive at consensus to develop strategies on how Blacks can work together to respond to concerns facing the community.

Al Mercury chairing a community meeeting

At around the same time, he and Rick Gosling led the way in establishing Community Unity Alliance (CUA) to assist visible minority groups become independent by providing office space, skills training and other resources.

Mercury was the CUA vice-president and secretary/treasurer at the time of his death.

“I will miss those 6.a.m. wake-up calls from Al who would have already gone through the three mainstream daily newspapers for that day and was ready to share an opinion on social issues,” said Gosling at the funeral.

Concerned about the upliftment of the Black community, former CUA Board Director Zanana Akande said Mercury always had ideas to approach problems and barriers.

“He was also very direct in the way he spoke and for that he might have been resented by a few people,” she said at the time of his death. “But he was honest and truthful.”

A voracious reader and book lover, Mercury spent a lot of time at the Central Library located then at College & St. George Sts.

“Like most people of African descent who were born in Toronto in the pre-war period, many of them lived in the area downtown around Bathurst and Spadina,” Taylor said. “But one of the central points at the time was the Central Library. There is a story that someone saw him on College St. and remarked, ‘There goes Al Mercury. He has read all the books in the library’.”

Noting that Mercury cared about the community, Taylor provided an example to demonstrate his generosity and commitment to serve.

“It was customary for us if we were at a restaurant to stay back after our Lions meetings and support the business establishment beyond just having our meals,” he noted. “While sitting at the bar one night around 11 p.m., I told Al about someone in our community who had a child and was in dire straits. He told me he would solve the problem and the next morning at about 6 a.m., Al called me, saying he was ready to go and knock on that person’s door and ensure they understood the community was willing and ready to support. Though he didn’t suffer fools gladly, he could put his personal feelings aside when there was a need for empathy and support. He loved his community tremendously.”

Al Mercury with his wife Wilma and their grand-daughter Alana at the 1994 Harry Jerome Awards

Mercury was recognized for his community contributions with a Harry Jerome Award in 1994, the same year that the late Malcolm Streete was recognized for leadership.

“I nominated Malcolm who said he wasn’t going to accept the award unless someone who has done if not more work but equally the same as he did got that opportunity to be a recipient,” added Taylor. “Malcolm spearheaded the nomination of Al.”

A Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada Reserve Officer for many years, Mercury is also survived by his wife Wilma, son Alan who is a Human Resources consultant with the City of Toronto and daughter Brandee who is retired in Surrey, British Columbia.