Exploring Black Nova Scotia's history through film

March 5, 2020

As the first high school graduate from Beechville in 1968 to attend university, much was expected of Sylvia D. Hamilton.

The Nova Scotian hasn’t disappointed.

A small rural community outside Halifax, Beechville was established by Black Refugees from the War of 1812 (they had liberated themselves to fight on the side of the British) and for the first four years of her elementary training, she attended a segregated school.

Hamilton said the only reference to Black people she had in school books was a short paragraph about ‘Negroes in Nova Scotia’, in a small Grade 5 text book. It was difficult for her to connect that passage to herself and the people she saw while growing up.

“The lack of information about Black people in Nova Scotia and Canada continued throughout my years of schooling and into university,” the award-winning filmmaker said. “I decided that if I really wanted to know that history, I needed to first speak with the elders in the communities and also dig into the archives and search for that information about myself. Once I started that search, I realized that if I could find ways to share what I was finding with others, then that would be an important goal and I could also reflect and give back that information to the many communities of people of African descent who also experienced being ignored or made invisible within the school curriculum.

“I also wanted to pay tribute to the ancestors because I realized when I started to dig deeply into the history how much courage my ancestors, particularly the Black Refugees from the War of 1812, had in order to do what they did. I wanted to make sure that sacrifice was understood.”

After graduating from Acadia University with her first degree, Hamilton started working in social and community development at an alternative school for high school dropouts in Halifax and with community-based organizations across the country through Company of Young Canadians in the 1970s and, in the 1980s, she managed programs at the federal department of Secretary of State in Halifax.

As a trained journalist, she worked for private radio stations and freelanced with the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) before transitioning to filmmaking to visually convey the life experiences of African Nova Scotians to the mainstream of Canadian arts.

Hamilton’s first documentary, ‘Black Mother Black Daughter’ explored some of the powerful women that shaped her life and Nova Scotia’s Black community.

She and Claire Prieto co-directed the project for the National Film Board (NFB) Atlantic Centre.

Released in 1989, it was the first film created by the Centre to employ an all-female crew.

“It was considered a ‘training’ film at the NFB at the time because no film had been made with a completely female crew,” Hamilton, who while working at Studio D of the NFB co-created a program – New Initiatives in Film -- for women of colour and First Nations female filmmakers, recalled. “I insisted that it was all female because the film grew out of a women’s group that I was part of.”

It took some cajoling to convince the strong Nova Scotia women that their stories mattered.

“I knew all of them and, over tea, they would tell me ‘I just did what I did’,” said Hamilton whose maternal grandfather was a watchmaker from Barbados. “They eventually agreed and it was quite an experience to go into their homes and create these moments where they were able to tell their stories. Subsequently in April 1989 when the film was launched, we had 500 people at the World Trade Centre in Halifax for the screening and an equal number outside waiting to get in. We did a second screening. That was unprecedented as far as I know and there are people to this day who tell me they couldn’t get in.”

The 29-minute documentary was screened across Canada, the United States and Europe.

While working on her first documentary, Hamilton wrestled with the large volume of material at her disposal and the variety of women whose stories were lining up.

Portia White was a story that she longed to tell.

Considered one of the 20th century’s best classical vocalists, White was raised in Halifax where she sang in the church choir as a child. She won a scholarship in 1939 to attend the Halifax Conservatory of Music and, two years later at age of 30, gave her debut concert at Eaton Auditorium in Toronto which placed her in the national media spotlight.

The first Black Canadian concert singer to be acclaimed internationally performed for Queen Elizabeth II in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island in 1964 before succumbing to cancer four years later in Toronto at age 56.

“Portia was a teacher in Beechville long before I was born and I always knew her name because my late mom, who was also a teacher in Beechville, told me about her,” said Hamilton. “However, I had no idea of exactly who Portia White was and how she did what she did. She was one of the women I wrote about in my original proposal––that was to be a one hour film -- that led to the half hour ‘Black Mother Black Daughter’, but I knew at some point I wanted to explore her story. I wanted to find a way to rescue her memory and answer some of those questions I had about how she became an artist in the 1940s.”

‘Portia White: Think On Me’, was released through her company, Maroon Films Inc., 20 years ago. ‘Think On Me’ was the English art song that White performed as a concert encore.

Hamilton, who started her research for the film in 1988, said that project was her most challenging.

“I started from scratch to think about how to tell that story,” she pointed out. “Normally, if you are making what might be called a biopic of someone, you either have a biography or autobiography to use as your basis to create your treatment or you might have the person—the subject—who you can interview to have as part of your story. I had none of that. So it was really starting from the bottom to think about how to tell that story. Fortunately, her family was enormously supportive and helpful. It took about 10 years to put that whole project together.”

Other important films that Hamilton directed include ‘Speak it: From the Heart of Nova Scotia’ (NFB) that voices the concerns of African Nova Scotian young people struggling with questions of identity, race and empowerment and was recognized with a Gemini Award in 1994 and ‘Against the Tides: The Jones Family’ that explores the history of Blacks in Nova Scotia through a family.

Through her company, she has directed and produced ‘Carrie Best: Champion For Human Rights’, ‘Thomas Peters: Man of the People’ which is the untold story of the Black Loyalist leader and his quest for freedom for Black Loyalists and ‘The Little Black School House’ that looks at segregation in Nova Scotia and Ontario schools.

“As someone who went to a segregated school, I was aware of them and the contributions especially of the teachers who did their best to educate us,” she noted. “Initially, I was going to do a major film about racism in Nova Scotia and in that film, I planned to look at young people and education and a whole range of subjects. I was working at the NFB in Halifax at the time and there was a fire that destroyed my research and work on the project. The only thing I had left was a small section of work that I could focus on and that is where the film, ‘Speak it: From the Heart of Nova Scotia’, came from.

“But I always wanted to explore Black education. As a result of that fire, I was able to think about placing my focus on a full film in the area of segregation in education, not just in Nova Scotia, but also in Ontario where there were segregated schools. My mom helped to set up a group of retired educators of segregated schools who met to talk about their experiences. They held a reunion that I attended and that set me to thinking that I really had to find a way to document this story.”

Aderonke Akande, the daughter of Canada’s first female Black Cabinet Minister Zanana Akande, was the Associate Producer of ‘The Little Black Schoolhouse’ and ‘Portia White: Think On Me’.

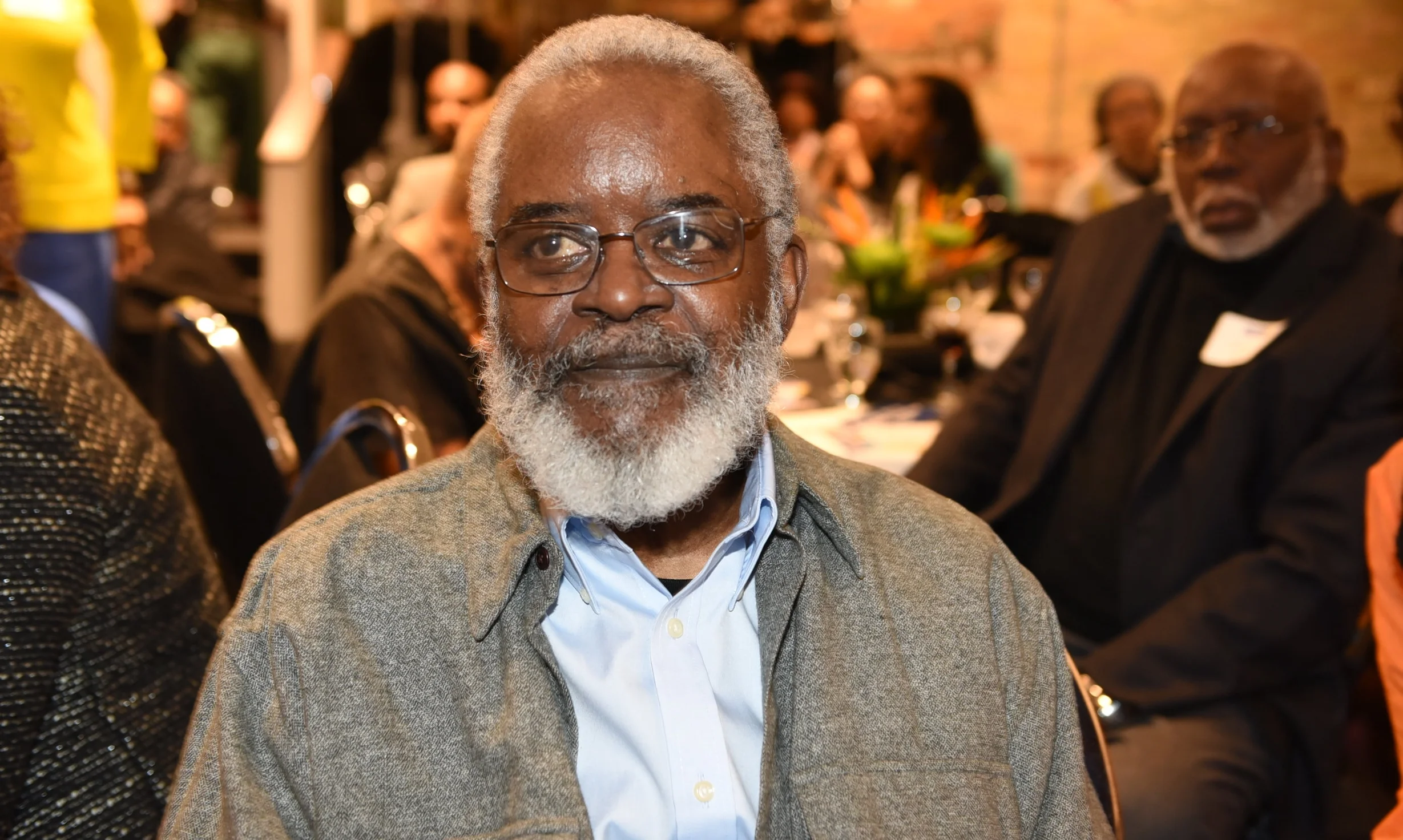

Sylvia Hamilton (Photo by Adams Photography)

A Professor in the School of Journalism at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Hamilton is also an acclaimed poet. Her 2014 collection, ‘And I Alone Escaped to Tell You’, was shortlisted for the League of Canadian Poets’ Gerald Lampert Memorial Award and the JM Abraham Poetry Award.

Over the last three decades, she has been honoured with myriad awards for her significant contributions. They include the CBC Pioneer Award, the AMTEC Media Festival Award of Excellence, the Atlantic Film Festival Rex Tasker Award for Best Atlantic Canadian Documentary, the Halifax Progress Women of Excellence Award and the Baha’i Community of Canada Race Unit Award.

Her latest is the 2019 Governor General’s History Award for Popular Media that honours individuals or organizations that have helped popularize Canadian History with the written word through publications, film, radio, television, theatre, voluntarism or the web.

“The award, named for historian Pierre Berton, is significant because it recognizes the body of work that I have created over many years, the objective of which was examining our full history and finding ways to communicate it to first a Black community audience and secondarily to anyone else who may want to listen in,” said Hamilton who has served on many non-profit boards, chaired arts-related juries and completed an appointment with the Heritage Minister's Expert Advisory Group for Canadian Content in a Digital World. “People in small towns, students in classrooms, universities or libraries have an opportunity to learn something about African-Canadian History that they may not have known before. Also, the award stands out because it is a unique one recognizing the importance of media in education and in our lives.”

Hamilton is also the recipient of honourary doctorates from Saint Mary’s, Acadia and Dalhousie universities. At Dalhousie, she served on the Transition Year Program (TYP) advisory board and supported the law school’s Indigenous Blacks & Mi’kmaq Initiative (IB&M).

To celebrate the university’s bicentenary in 2018, Hamilton made the list of 52 Dalhousie Originals who have inspired, strengthened and at times challenged their university, communities, fields of study and the broader world.

She completed her Master’s at Dalhousie in 2000. Her thesis, ‘African Baptist Women As Activists & Advocates in Adult Education in Nova Scotia’, examines the activities of African Baptist women in the latter half of the 19th century when there was an expansion of Black churches in the Maritimes.

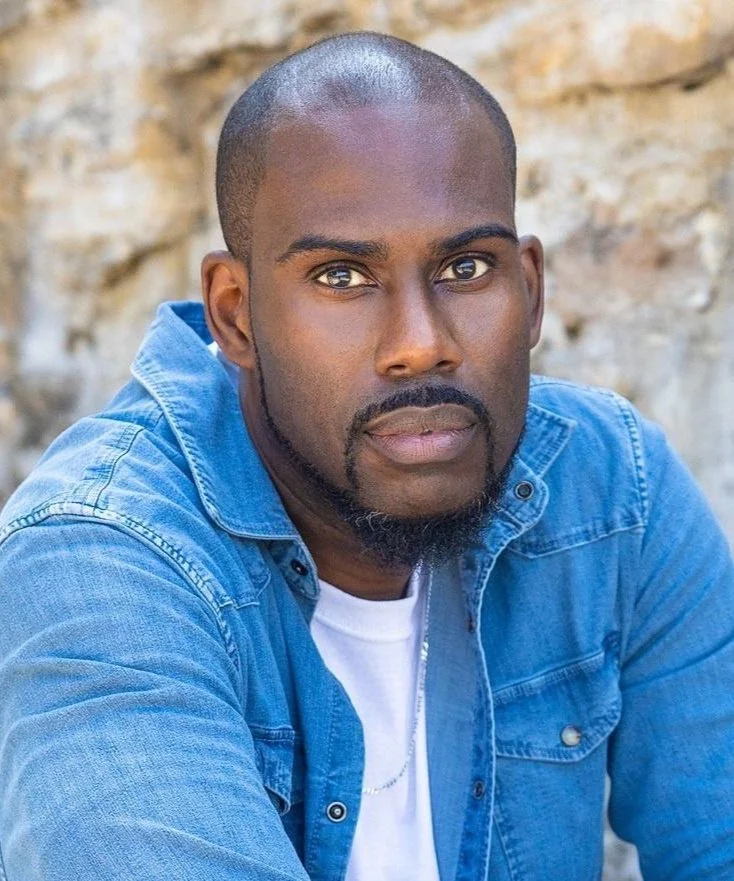

Christina Smith (l) was the recipient of the Sylvia Hamilton Award presented at the 2019 Viola Desmond celebratory event at Ryerson University

Over the years, Hamilton has mentored many Nova Scotians, including journalist Sherri Borden Colley and Quenta Adams-Coward who is Dalhousie University’s Student Affairs Director.

“Sylvia took a considerable amount of time to nurture my development and I was fortunate to work with her on a few projects over 25 years ago when I had expressed an interest in the creative arts,” said Adams-Coward. “On those projects, she was always teaching either directly or indirectly. She always had time for questions, helping build my confidence in the profession by assigning me tasks which were key to the projects and she invited my feedback when I didn’t think I had anything of value to offer. Although my personal and professional life led me in another director, the impact Sylvia made is long lasting. She has both natural curiosity and undeniable intellect and is truly a gem.”