Exhibition explores role of African women in photography

November 2, 2019

Seeing The Walther Collection in New York for the first time a decade ago was awe-inspiring for Sandrine Colard.

An art foundation dedicated to the critical understanding of historical and contemporary photography and related media, the Collection – through a program of international exhibitions, in-depth collecting, original research and scholarly publications – aims to highlight the social issues of photography and expand the history of the medium globally.

“What I found very interesting about this Collection is that it is so vast and you can always produce a new and exciting show because there are so many different facets to the exhibition,” said the Rutgers University-Newark art historian. “There’s always a rediscovery and you always feel like you have never seen the photos before because they are represented to you in a new way.”

David Goldblatt, A Farmer’s Son with his Nursemaid, Heimweeberg, Nietverdiend, Western Transvaal, from the series Some Afrikaners Photographed, 1964 (printed 2010), gelatin silver-print. Courtesy of Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Colard was thrilled when she got the call to curate the major African portraiture at the Ryerson Image Centre (RIC) that explores the role of women in photography.

The RIC collaborated with The Walther Collection to present, ‘The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture’, that features contemporary work by female artists alongside 20th century studio portraits and early colonial images and albums.

A.C Gomes & Sons, Natives (sic) Hair Dressing, Zanzibar, Tanzania, late 19th century collodian printed-out print. Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

African women bodies have often been objectified and fetishized throughout the history of photography. This exhibit shifts the focus towards women gazes and highlights female acts of looking that challenge the male-dominated narrative of the medium. Showcasing over 100 works by female and male practitioners from across Africa, the exhibition emphasizes the ways women see and present themselves while tracing how they moved from being eloquent photographic subjects to adopting positions behind the camera.

Colard said the exhibition, which runs until December 8, is very significant and long overdue.

“Most of the images of African women that I had seen in my life were as objects of the gazes of others, but rarely of their own and that had my head spinning,” she said. “When I was approached by Gaelle Morel to curate a show about African photography from The Walther Collection, the subject of the exhibition became instantly clear to me. Even though in this exhibition you will be able to contemplate among the most beautiful images created of African women, the key here is to remember that they are also the ones looking back at the photographer, of themselves, of the world and today at us. I wanted this show to recognize that power not just in the present time, but also historically a power that they retained even in the most difficult circumstances.”

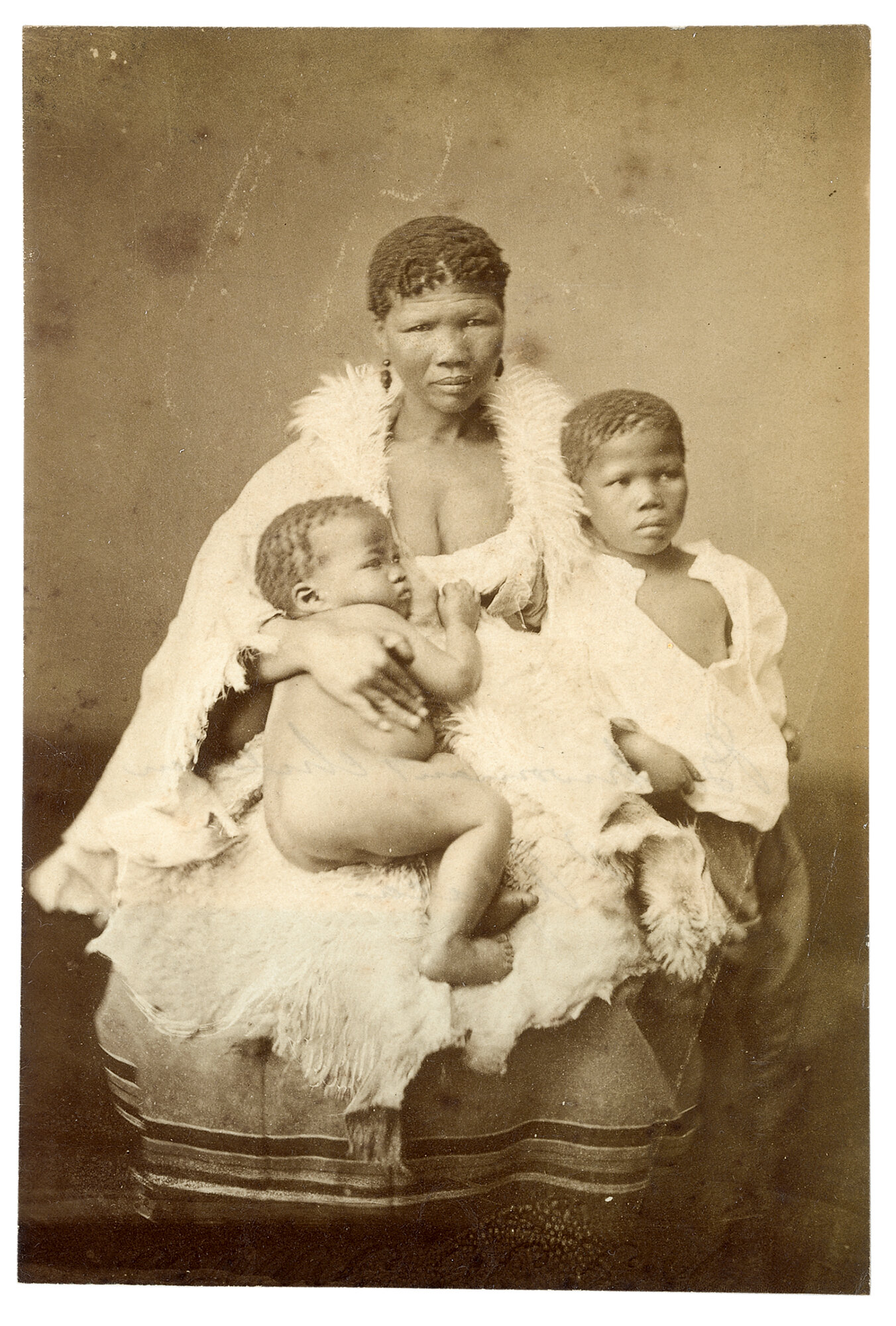

Samuel Baylis Barnard, Bushwoman (sic) and Children, South Africa (Portrait of Ikweiten ta //ken), 1874-1875. albumen print mounted on paper. Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

The exhibition is divided into three parts. The first showcases 19th and 20th century photographic prints, cartes de visite, postcards, albums and books from Southern and Eastern Africa while the second section features women’s portraits dating back to the 1950s. The third part highlights significant African female and non-binary artists who have emerged since the 1990s.

“By privileging women’s perspectives, both in front of and behind the camera, this groundbreaking exhibition confronts the canons of art history and allows for new narratives,” said Morel who is the RIC Exhibitions Curator. “We are thrilled to celebrate the work of so many leading African artists, many of whom are being shown in Canada for the first time.”

Launched nine years ago, The Walther Collection has done 15 exhibitions featuring African photography.

“What you see here is going deep into a very specific segment,” said art collector Artur Walther. “It is very unique. These images were never really researched, reflected on or discussed in a broader discourse.”

Artur Walther

Created in part in 2012 to display the nearly 292,000 ‘Black Star’ anonymous donation, the RIC stands out for Colard because ‘it combines a beautiful exhibition space, a research centre, large audience of students and it’s right in the middle of the city’.

“For me, it is really the perfect combination of what an art institution should be,” said the Modern & Contemporary African Arts specialist. “It’s the perfect spot where I like to have an impact by what I do.”

Where did Colard’s interest in post-colonial art and imagery come from?

“My mom is Congolese and my dad is Belgian, so I would say I am the product of a post-colonial relationship,” said the Brussels-born educator. “It has always been part of my interest for my own history but also because it’s not just my history, but that of Europe, America and the world. There are very few parts of the world that have not been involved in one way or the other in Africa. As a student, I became more and more interested in atomic art. What’s interesting is that a lot of people have told me that very often as a Black European, your introduction to these post-colonial questions is through the United States and African-American cities.”

Unidentified photographer, Zulu Mothers, South Africa, late 19th century, gelatin silver printed-out print. Courtesy of The Walther Collection

Colard is a huge fan of late American novelist, playwright and activist James Baldwin.

“It is really through reading his books that I became interested in what had been produced by the numerous Black intellectuals in Africa and Europe that I decided to do my doctorate in Art History,” she added.

Completed three years ago at Columbia University, her thesis was, ‘History of Photography in the Colonial Congo’.

Based on research carried out in Belgium and in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, this dissertation is the first in-depth study of a history of photography in the Congo and the first comprehensive history of photography within a single colonial regime.

Jodi Bieber, Babalwa, from the series Real Beauty, 2008, inkjet print @The artist, Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

“It looks at images produced by Europeans and family albums by Congolese families between 1885 and 1960,” she added. “It is really fresh material. When I was doing research, people were very pessimistic about my ability to find images. They thought there was no such thing as a Congolese photographer prior to 1970. Though it wasn’t easy, I found families who kept images from as early as the 1920s. Then it became the perfect counterpoint to the image that had circulated the most about the Congo, meaning images by the colonial powers.”

Colard’s dissertation is being turned into a book.

Zanele Muholi, Miss D’Vine 11, from the series Miss D’Vine, 2007, chromogenic print @ The artist. Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Capetown and Johannesburg