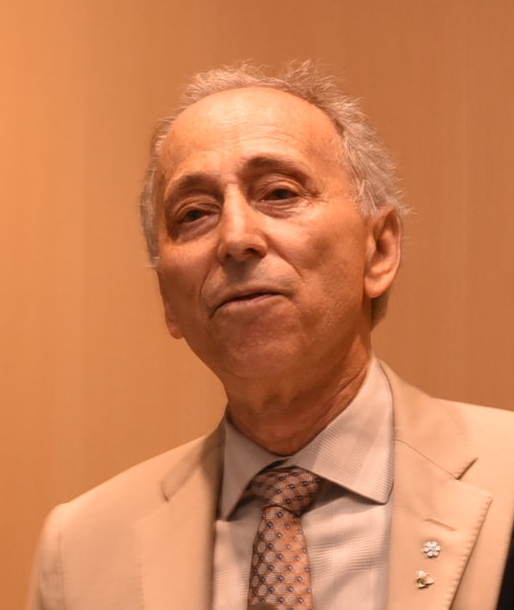

Bajan high school was platform for Dr. Fields to become an oncology expert

May 10, 2018

He taught high school mathematics and chemistry for three years, considered a diplomatic career after returning to Barbados in 1966 with a natural science degree from Cambridge University where he worked for a year as a technologist, and was persuaded to become a medical doctor.

In the end, Dr. Tony Fields settled on oncology and became an expert in the field in Canada.

Instrumental in the creation in 2010 of the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (pCODR) which is an evidence-based cancer drug review process, Fields was recently recognized by the Canadian Agency for Drugs & Technologies in Health (CADTH) with the Dr. Jill M. Sanders Award of Excellence in Health Technology Assessment.

CADTH president and chief executive officer Dr. Brian O’Rourke said Fields’ impact on cancer care in Canada can’t be overstated.

“He is a compassionate physician, an accomplished researcher, a leader and a visionary,” said O’Rourke. “His drive to improve patient care extended from the bedside in Alberta right across the country and his determination helped lay the foundation for Canada’s robust and internationally recognized approach to assessing cancer drugs.”

The founding chair of the pCODR expert review committee, Fields continued as the chair when the pCODR was transferred to the CADTH four years ago.

“It’s wonderful to get a national award and I am overwhelmed by the honour,” he said. “However, the work for which I am being honoured involved a lot of talented people that I led. Even though I have been singled out, this is a collective honour because so many people had input into the success of that initiative.”

A graduate of Harrison College which produced five of Barbados’ seven Prime Ministers, Fields said the high school provided him with the grounding to be successful anywhere in the world.

“That’s what that institution does for its students,” he noted. “Going to Harrison was a major branch point in my life.”

His classmates included Dr. Carlisle Boyce who is the executive director, industrial & transportation business with 3M Asia Pacific and the late distinguished scientist Dr. Oliver Headley who designed the first and largest electrical grid system using solar energy that’s installed at Harrison’s Cave in Barbados.

Fields still has fond memories of Headley who died six years ago.

“We often fooled around trying to make homemade rockets,” he said.

On his return to Barbados after graduating from Cambridge, Fields met and married CUSO International (formerly Canadian University Services Overseas) Canadian worker Pat Stewart who was on a two-year assignment to the Caribbean island.

At the end of the volunteer service in 1968, they decided to settle in her home province of Alberta.

With an interest in science, Fields secured employment as a chemistry lab technologist at Stelco that had steel plants at the time in Edmonton.

“I couldn’t teach in Canada because my degree was not in education and I was considering if I should go back to school to get that degree and pursue a teaching career like my mother and other family members or do further work in science,” he said.

Fields followed his wife’s suggestion to enrol in the University of Alberta vocational counselling program that was free and received a 95 per cent pass mark in the aptitude test, including one with 400 multiple choice questions.

“A few days after the test, a counsellor at the debriefing said I had done so well that I should consider becoming a physician,” he recalled. “The only problem was I didn’t want to be a doctor because I was 25 years old at the time and didn’t want to invest another six years in school. This guy, however, was persuasive and he said, ‘Do you think when you are 70, that would make a difference’. When I told him I still wasn’t prepared to put in the time, he asked if I knew how old Albert Schweitzer (renowned medical missionary) was when he started medical school. I didn’t.”

He was 35.

In his first year in medical school, Fields cured two mice during a session in which students injected the small rodents with experimental cancer and treated them with chemotherapy to try to cure them.

Thrilled with his accomplishment, he asked to take the mice home as pets.

“I love animals, but the instructor said no to my request,” he recalled. “When I asked if I could get some experience during the summer in his lab, he said yes.”

While in medical school at the University of Alberta, Fields realized his calling was in internal medicine.

“That has to do with the medical treatment of disorders of different systems like heart, stroke and neurological,” he said. “That is what I wanted to do and it was a major shift in my career path. I paid attention to cancer and would go to listen to visiting speakers even though I wasn’t thinking of becoming a career specialist. But during the years of training to be an internist, I found that I really had a special connection with cancer patients. I found it easy to talk and connect with them.”

In medical school, Fields was assigned to the oncology section headed by Dr. James Goldie who passed away last year. He oversaw the opening of the British Columbia Cancer Research Centre in 1979 and, with Dr. Andrew Coldman, developed the Goldie-Coldman Hypothesis to explain treatment resistance in cancers and to develop schedules to optimize the effectiveness of chemotherapeutic agents.

“He made this aspect of medicine fascinating,” said Fields who specialized in gastrointestinal oncology in his clinical practice and was chosen in 2013 by the Canadian Association of Medical Oncologists to present the Pioneer Lecture at their annual scientific meeting. “When in my third year the chief of medicine told me I should consider becoming a medical oncologist and there would be a good chance of me having a job there, I immediately changed my training pathway from internal medicine to the oncology stream.”

Fields trained in internal medicine and medical oncology at St. Michael’s Hospital and the Princess Margaret Hospital respectively in the University of Toronto system before joining the University of Alberta faculty and the medical staff of the Cross Cancer Institute in Edmonton in 1980.

During his time as vice-president of cancer care with Alberta Health Services, he was responsible for the province’s tertiary and associate cancer centres, community oncology programs and cancer research programs.

Fields spearheaded an investigation into a fatal chemotherapy overdose that led Alberta to revise procedures for the administration of some cancer drugs.

Denise Melanson died in 2006 at Edmonton's Cross Cancer Institute after a pump that was supposed to deliver fluorouracil, a drug used to treat tumours over four days, was given to her over four hours along with cisplatin which is another chemotherapy drug.

He previously held several administrative positions within the former Alberta Cancer Board, including director of the Cross Cancer Institute and vice-president with responsibility for medical affairs and community oncology.

Since stepping down as Alberta’s top cancer administrator in 2011, Fields and his wife of 51 years have been spending the month of February in Barbados.

He was appointed to the Order of Canada six years ago.