50 years after her death, Portia White exhibit brings family together

February 8, 2018

For almost half his life, Kevin Gray had no idea that he was closely related to contralto Portia White considered one of the 20th century’s best classical vocalists.

His father, Jimmie Gray who is 83 and resides with his wife Marguerite in Halifax, is the only child of White who gave up him up as an infant to a maternal relative.

He was never legally adopted and didn’t acquire a birth certificate until he was 34.

It wasn’t until Gray relocated to Toronto nearly three decades ago that he learnt of White through relatives.

She succumbed to cancer on February 13, 1968 in Toronto at age 56.

“I figure that having a child wasn’t one of those things that she was planning on at the time,” said Gray who attended the opening of the Portia White exhibit last Saturday at Don Heights Unitarian Congregation (DHUC). “My dad is very proud and never talked about his upbringing and his biological mother. I am getting the idiosyncrasies of the relationship between him and her from people like Sheila White – Portia’s niece -- and her late mother Vivian who kept in contact with my father.”

Gray met Sheila White for the first time at the launch. They had communicated by telephone and exchanged emails prior to the meeting where he saw the first picture of his paternal grandfather.

Dr. Hartley Rollock, a Barbadian who did his medical studies at Dalhousie University, died in May 1993 and is buried in Northern Ireland.

“My father has never seen a picture of his father before,” said Gray who turns 60 this year. “For him, this will be a revelation. It’s something he has never known and always wanted to know.”

One of six siblings (a brother is deceased), Gray took his youngest child – five-year-old Shawn Gray -- to the exhibit featuring recordings, letters, photos and concert programs.

Kevin Gray, the grandson of Portia White, and his five-year-old son Shawn

“I listen to Portia’s music and am very proud of her accomplishments,” he pointed out. “I am going to bring my two older kids ages 10 and nine to the exhibit so they would get to know more about our family history. I don’t want them to be in the dark like I was when I was growing up. It would be good for them.”

Unlike Gray, Dr. George Elliott Clarke knew at a very young age about the prowess of White who was his great aunt and the first Black Canadian to achieve prominence in the arts.

“My father insisted that his three sons knew about Portia White all the time,” he said. “We grew up understanding very well who we were related to. The example of Portia White for me and my siblings and our entire community was stellar. Whenever we felt that the larger society wasn’t giving us our due, it was important to be able to say to ourselves that our great aunt sang before Queen Elizabeth II. That’s special.”

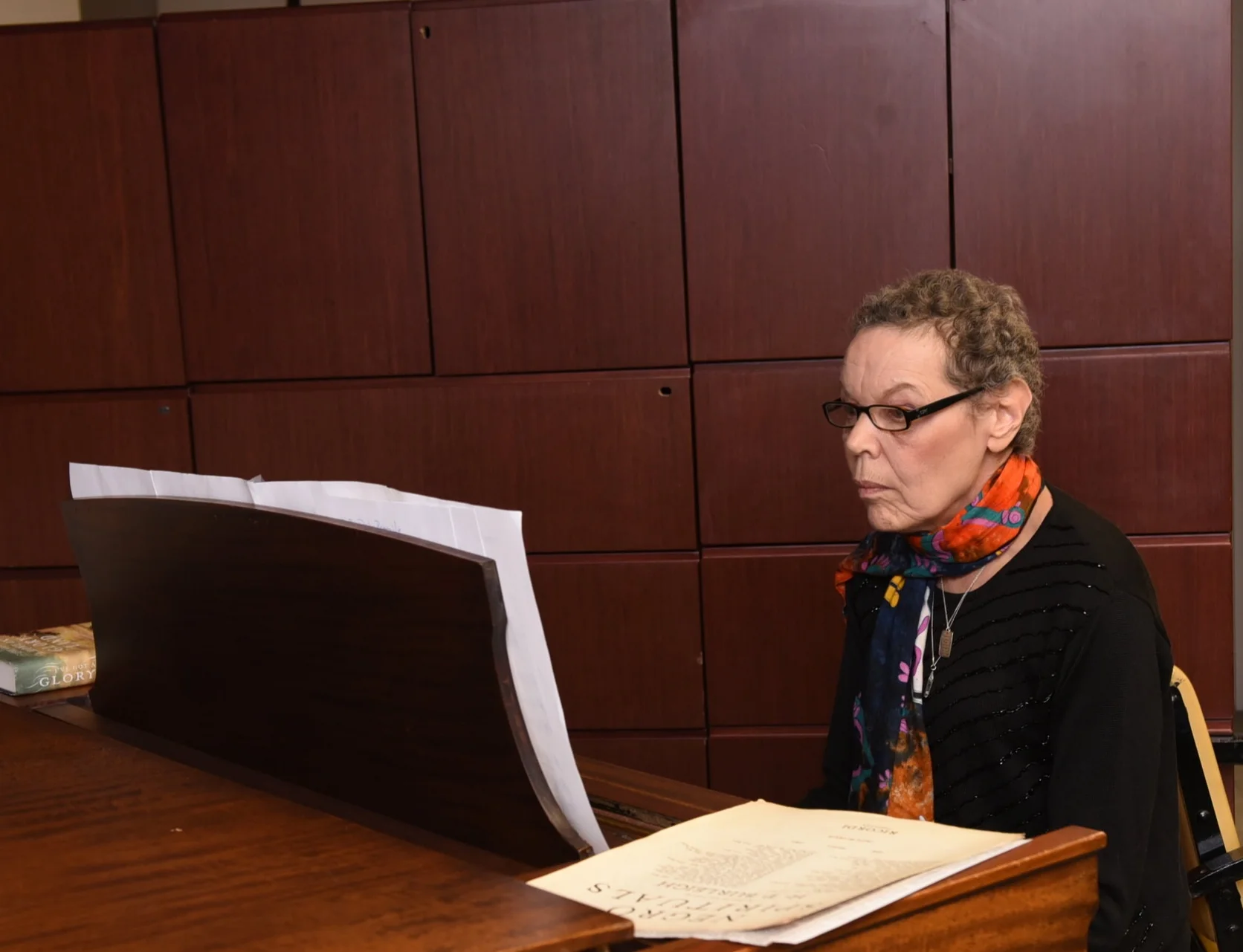

Dr. George Elliott Clarke

Clarke’s father – William Clarke – was a self-taught intellectual and artist who died in 2005.

Raised in Halifax where she sang in the church choir as a child, White won a scholarship in 1939 to attend the Halifax Conservatory of Music and, two years later, made her debut at age 30 in Toronto.

The first Black Canadian concert singer to be acclaimed internationally performed for Queen Elizabeth II in Charlottesville, Prince Edward Island in 1964.

Clarke, the E.J Pratt Professor of Canadian Literature at the University of Toronto, is proud that his great aunt helped introduce audiences around the world to the particular blends of music that she grew up with and loved.

“I am extremely heartened by the fact that she loved singing the spirituals,” he noted. “As much as she sang the classical art songs, when she committed to singing the music which came from outside the conservatories, the salons and the aristocratic patronage, that gift of Negro song registered with everyone who heard them just as well and as deep as any melodies or song by Beethoven or Mozart or even Duke Ellington for that matter.”

‘Celebrating Portia White…50 Years On’, is organized by the DHUC in collaboration with the Ontario Black History Society (OBHS) and the White family.

They are seeking support to send the exhibit to other parts of Canada before it goes to a permanent archival home. Some of White’s items are already housed in the Library & Archives Canada, the National Gallery of Canada, the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia, the OBHS and Dalhousie, Acadia and Stanford universities.

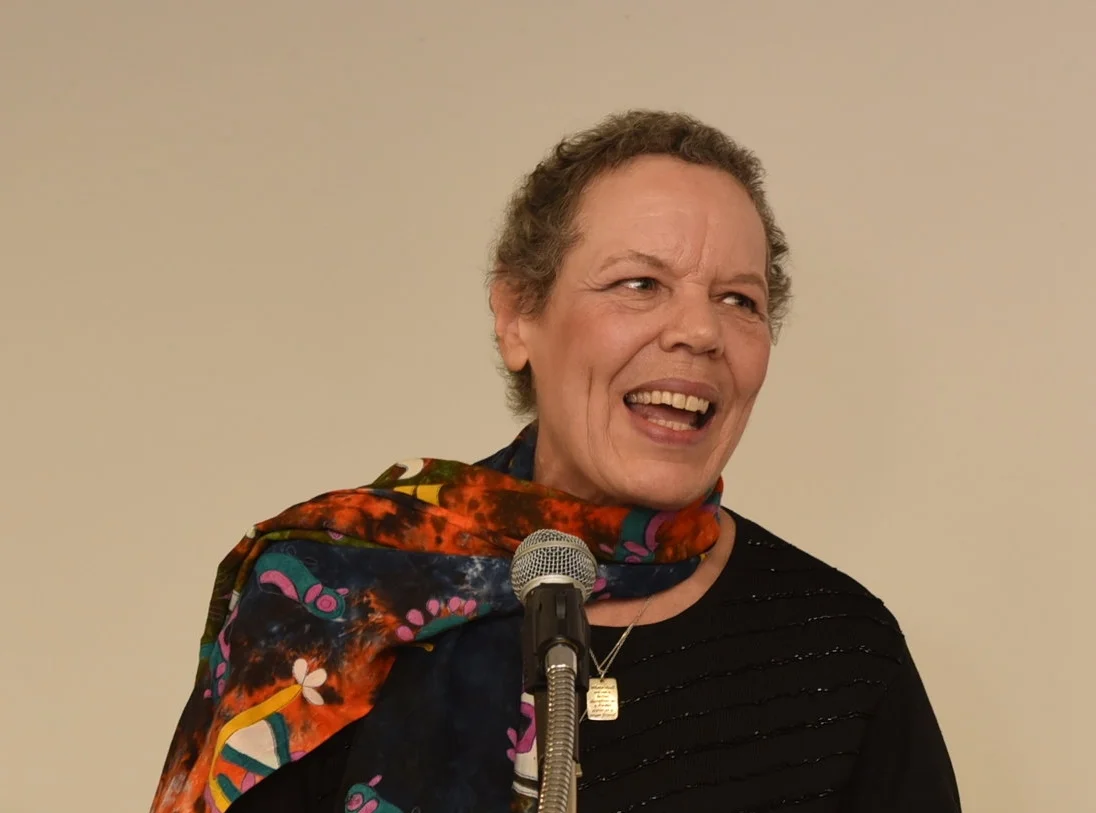

Sheila White

Clarke acknowledged the organizers for keeping White’s legacy alive through the exhibit.

“What has happened here in this particular religiously inspired space is the formation of an archive,” said the former Canadian parliamentary poet laureate and seventh generation African-Canadian who is descended from African-American refugees from the War of 1812 who escaped to the British and were relocated to Nova Scotia. “Yes, this is related to Portia White, but beyond her a history of struggle for equality and how essential it is that we have access to these archives of histories of struggle.

“…For any of us who are engaged in struggles of equality, egalitarianism, civil liberties and human rights, it’s absolutely vital that we have these records of these struggles available to us. The archives are probably the most important public trust that we have next to the health care infrastructure in terms of maintaining public memory of what is important in a democracy in terms of ensuring equal rights for all. This exhibit is actually a transcendent exhibit because it helps reminds us all of the deep necessity of having access to archives.”

Clarke argued that White stood just as tall and powerful for notions of egalitarianism as the multi-talented Paul Robeson who died in 1976 at age 77.

The son of a runaway slave was a scholar, bass-baritone concert singer, actor, writer, multi-lingual orator, lawyer and an accomplished athlete who earned 13 varsity letters in football, basketball, track and field and baseball. He was the third African-American accepted at Rutgers and the only Black student during his time on campus.

A prolific writer for leftist and progressive periodicals, Robeson was a regular visitor to Canada. He performed at Maple Leaf Gardens, Massey Hall and at the Peach Arch concerts and appeared at Communist Party of Canada events.

“As his voice was registered in the struggle for freedom, so was hers,” said Clarke who holds eight honourary degrees. “As she paraded across those concert stages around the world, she was echoing in a sense Paul Robeson’s similar attempts to sing the world to greater unity through song and through music.”

In 1999, Canada Post issued a millennium stamp bearing the image of Portia White who was named ‘A Person of National Historical Significance’ by the Canadian government four years earlier.

White came from good stock.

Her father, William White, led the formation of the Number 2 Construction Battalion – the only all-Black expeditionary force in Canada’s military history – that celebrated its 100th anniversary two years ago. He became its chaplain, the first Black in the British Empire to hold a commissioned rank and the first Black student to graduate from Acadia University.

While overseas, White – the first Black to receive an honorary doctorate from Acadia University shortly before his death in 1936 at age 62 – wrote a war years’ dairy that became the subject of a film, ‘Honour Before Glory’, which was produced by his great, great nephew Anthony Sherwood.

The Portia White public exhibit to coincide with Black History Month is open free to the public on Tuesday February13, 20 and 27 from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., on Saturday February 10, 17 and 24 from noon to 4 p.m. and on Sunday February 11 and 25 from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m.

The DHUC is located at 18 Wynford Dr., Suite 102.