Black Power salute celebrated 50 years later

October 22, 2018

There are some images that are forever imprinted in the mind.

Who would forget that picture of Muhammad Ali triumphantly standing over a dazed Sonny Liston after their second fight in 1965, Ali sitting at table with three of the greatest athletes – Jim Brown, Kareem Abdul-Jamar and Bill Russell -- at a meeting at the Negro Industrial Economic Union office in Cleveland in 1967 to support Ali after he refused to be drafted or Jim Redmond helping his son Derek Redmond – who suffered a hamstring injury 150 metres into the semi-finals of the 400-metre event at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics – cross the finish line?

A year later at the Mexico Olympics, Americans Tommie Smith – who won the gold medal in the 200-metre contest – and bronze medallist John Carlos mounted the awards podium shoeless with a black glove on their hands. Smith had a black scarf around his neck.

“Once we decided on the ‘symbology’, we had to figure out how to get our hands on the symbols,” Carlos says in ‘The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment that Changed the World’. “Fortunately, my wife Kim (she committed suicide four years after they broke up) had the beads and was down with our plan all the way. Tommie’s wife at the time had the black gloves. It’s an interesting detail of history that she had only brought the gloves to Mexico City because Tommie had told her that if he had to shake Avery Brundage (the late International Olympic Committee president at the time) hands, he didn’t want to have to touch the old man’s skin. Of course, we had our own black socks which were the style at the time.”

Silver medallist Peter Norman of Australia wore the official Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) badge to show his support for the Black liberation struggle.

As the American anthem was played after the medal presentation, Smith and Carlos – pall bearers at Norman’s funeral (he succumbed to a heart attack) in October 2006 in Melbourne -- raised their gloved fists and bowed their heads.

Time Magazine considers it the most iconic sports photograph ever taken.

In 2005, San Jose State University honoured Tommie Smith and John Carlos with a sculpture depicting their famous gesture (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

Smith later told late sports journalist Howard Cosell that his raised right hand and Carlos’ left stood for the power and unity respectively in Black America.

“Together, they formed an arch of unity and power,” added Smith who is the only athlete to hold 11 world records simultaneously and the first sprinter to win an Olympic gold medal in the 200-metre event under 20 secs. “The black scarf around my neck stood for Black pride. The black socks with no shoes stood for Black poverty in racist America. The totality of the effort was the regaining of Black dignity.”

Smith, who held 13 world records, also confided to Dr. Harry Edwards, who organized the Olympic boycott, that they bowed their heads to pay tribute to America’s Black liberation struggle activists, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X who were assassinated.

Eleven months before the 1968 Olympics, Edwards launched the OPHR to advocate a Black boycott for the Games.

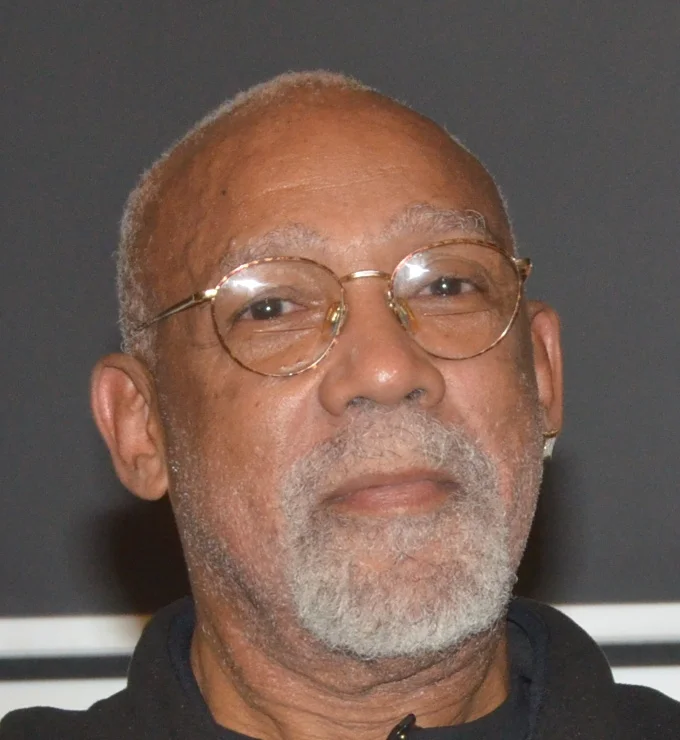

To mark the 50th anniversary of the silent act on October 16, Edwards, Smith and Carlos were reunited last week at San Jose State University (SJSU) which is the birthplace of the OPHR.

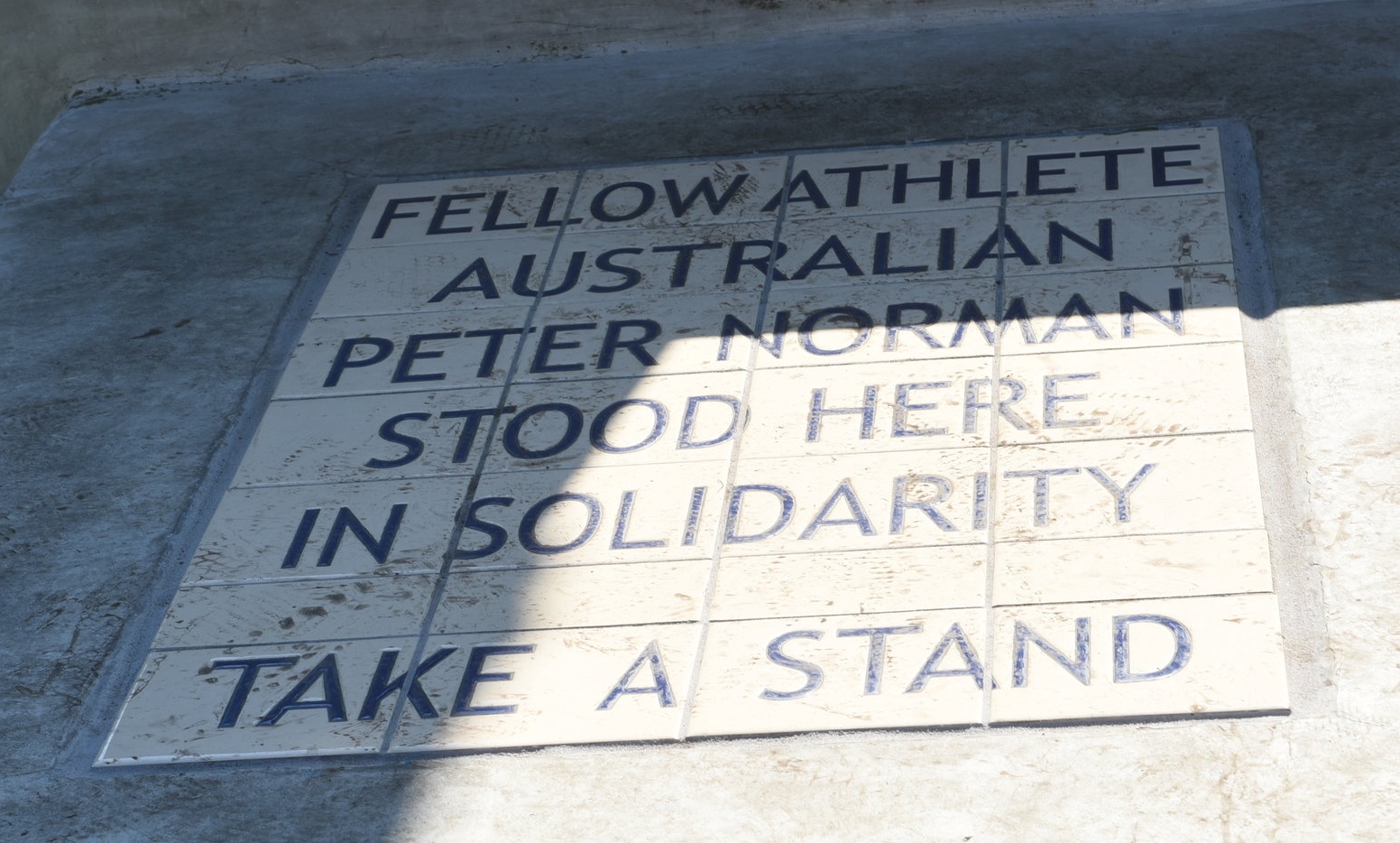

The plaque is beside the 22-foot statue in the centre of the San Jose State University campus (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

It was also at SJSU also that Edwards -- he captained the basketball team and set records in the discus -- graduated with a sociology degree in 1964 and was a visiting professor from 1966 to 1968 and Smith completed his undergraduate degree in social sciences in 1969. Carlos was on the campus for a year after transferring from East State Texas University (ESTU) where he was awarded a full scholarship in 1967.

When the ESTU coach took aim at the 1967 Winnipeg Pan American Games 200-metre gold medallist, referring to him as ‘boy’ and ‘that Negro Fella’ in front of his wife and little girl and also tried to convince the Harlem-born sprinter that the reason that Blacks are superior athletes is because they have extra bones in their body, the proud student-athlete made up his mind he was not going to be target practice, even if it meant walking away from a scholarship.

Fed up and frustrated, he called Edwards who at the time opposed the United States Olympic Committee, the political establishment and the mainstream media, complaining; ‘Can’t take the heat here man. Don’t like the snubs, the restricted housing, the way they mistreat my wife, the whole phony deal.’

When Edwards asked what he was going to do about it, Carlos replied, ‘Join a freedom movement somewhere, maybe.’

That’s how he ended up and SJSU which was a hotbed of 1960s activism.

The punishment for the 1968 Black Power protest was swift and extreme for Smith and Carlos.

Within 48 hours, they were suspended by U.S. Olympic Committee and evicted from the Olympic Village. On their return home, they were ridiculed as traitors.

Peter Norman declined to be depicted in the installation shortly before his death in 2006 (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

Smith received death threats and was forced to scrape for a living to support his family. His first marriage eventually succumbed to the tremendous strain. He had a brief stint with the Cincinnati Bengals of the National Football League (NFL) back-up squad before landing on his feet as a track & cross country coach and physical education professor at Santa Monica College. He retired in 2005 after 27 years.

Carlos begged, borrowed and stole to provide for his family.

With no football experience, he landed a NFL job with the Philadelphia Eagles. When he suffered a serious leg injury, curtailing his enticing speed and subsequently activating his release, Carlos was offered an opportunity by then Montréal Alouettes general manager J.I Albrecht to compete in the Canadian Football League (CFL).

That short-lived experiment lasted long enough for him to secure Canadian citizenship for his family. But without a job to support them, he reluctantly returned to the United States in search of meaningful employment.

A desperate Carlos tried in 1973 to resurrect his CFL career with Toronto, but a phone call one morning from his children indicated that things back home weren’t right. He immediately returned home to find that his wife had moved out of the family residence leaving him with just a bar stool and coffee pot.

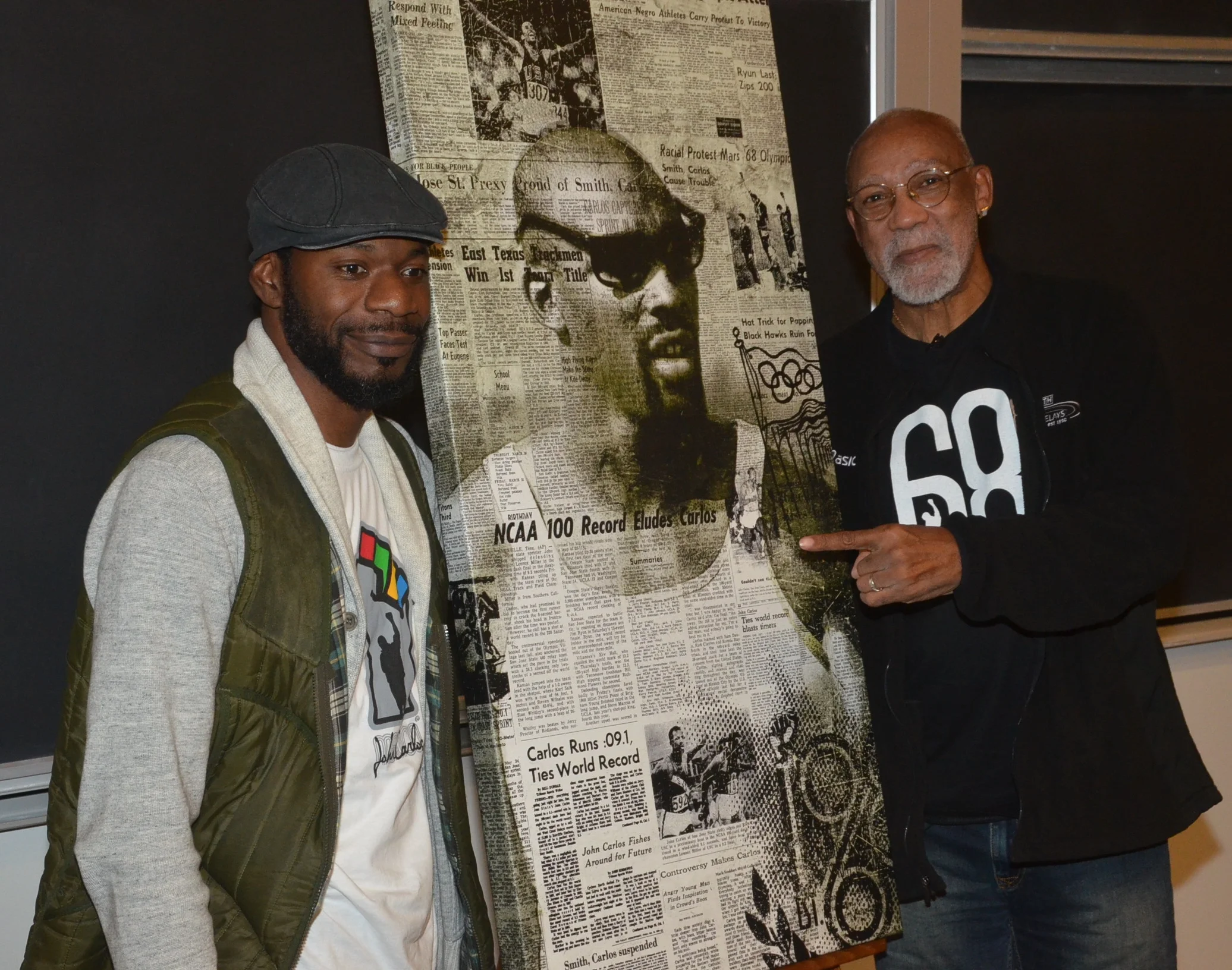

Thirty eight years after hitting rock bottom, Carlos -- the first athlete to run 100-metres in 9.9 secs. and the 200 metres in 20 secs. on the same day at the Indian Summer Games in Lake Tahoe, California in September 1969 -- set foot in Canada for the first time in November 2011 to promote his book.

Mark Stoddart (l) presented John Carlos with a personalized painting during his November 2011 visit to Toronto (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

He said he had a premonition at a young age of the events that unfolded at the 1968 Olympics.

“At age seven, I had a vision in which I saw myself standing on a box with my hand raised in front of a whole group of people applauding,” Carlos noted. “The next thing I knew, they were cussing and spitting at me and my happiness turned to anger. I remember telling my dad I was in a movie and something I did made the people become mad. Who would know that 15 years later, that vision would become a reality in Mexico City?”

Despite the hardships, Carlos -- whose mother was born in Jamaica and raised in Cuba before migrating to the United States -- never wavered from his stand against oppression and other forms of injustice.

During last week’s three-day celebration at SJSU, Smith and Carlos participated in atown hall meeting that reflected on OPHR’s 50-year legacy and its connection to the current wave of athlete activism and theywere bestowed with the university’s highest honour.

Again, Edwards paid tribute to Smith and Carlos for taking a stand against injustice.

“It was in the wake of assassinations, of cities burning,” he said. “…You need to understand that to understand the depth of their commitment. These two men, along with Lee Evans (he won gold medals in the 400-metre and 4x400-metre events at the 1967 Winnipeg Pan Am Games and the 1968 Mexico Olympics), are among the most courageous men I have had the privilege of being associated with and working with.”

Over the years, professional athletes have paid a steep price for their activism.

Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, who converted to Islam during his first season with the Denver Nuggets, refused to stand for ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ before National Basketball Association (NBA) games. After the protest that resulted in a one-game suspension in 1996, he played just three more seasons and started in 62 games.

After 10 seasons in the NBA, outspoken social justice activist Craig Hodges – who visited the White House dressed in a dashiki after the 1992 Chicago Bulls championship season and presented a letter to then president George Bush Sr. urging him to address the concerns of poor and minority communities-- was blackballed and never played in another NBA game.

Colin Kaepernick suffered the same fate after choosing in 2016 to kneel on one knee rather than stand while the United States national anthem was being played before the start of NFL games to protest police brutality against Blacks. After opting out of his contract with the San Francisco 49ers and becoming a free agent in March 2017, NFL teams refused to sign him.

Kaepernick has been effusive in his praise of Smith and Carlos for inspiring him to take a stand against injustice.

In a tweet, he wrote, ‘Thank you Tommie Smith & John Carlos 4 the sacrifices you made on this day 50 yrs ago. They have laid the foundation 4 the advancement of many others at their own personal expense, & have done it gracefully & unapologetically! We will never be able 2 repay you 4 what you have done 4 us!’