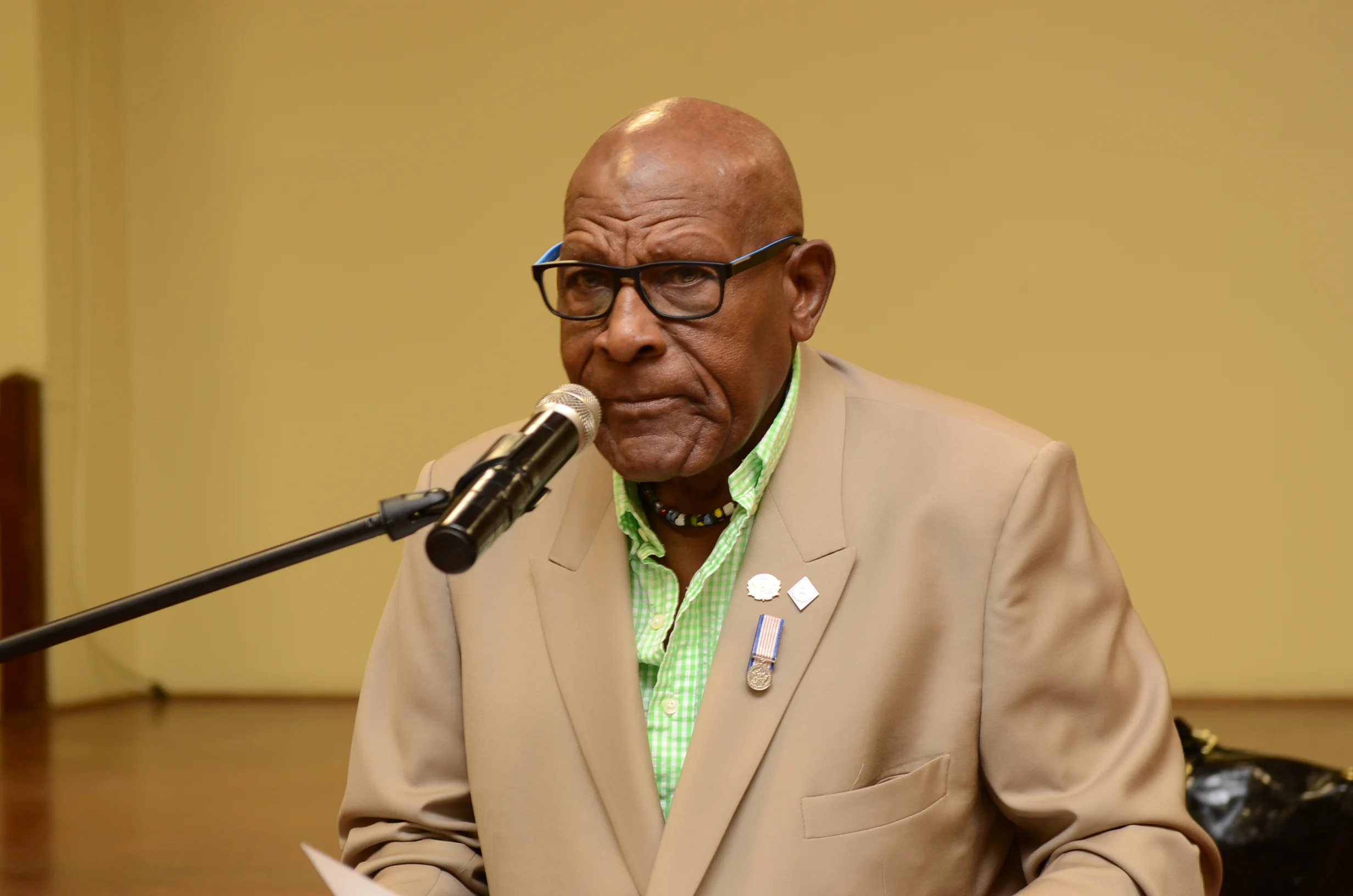

Entrepreneur/ philanthropist Denham Jolly releases autobiography

February 19, 2017

Worshipping celebrities and famous people can be gratifying and unpleasant.

After experiencing the distasteful side of hero worship years ago, businessman and community leader Denham Jolly vowed he would never ‘suck up’ to superstars again.

An avid tennis fan who has attended the four major Grand Slams in Australia, France, England and the United States, Jolly idolized the late Arthur Ashe who was the first Black player to win at Wimbledon, Melbourne and Flushing Meadow.

After Ashe’s victory in a tournament in Toronto, the octogenarian approached his idol to offer his congratulations.

“I tried to shake his hand, but he pushed me out of his way,” Jolly recalled.

That experience left a bad taste in his mouth.

“After that, I had no time for celebrities,” he said.

FLOW 93.5 FM, Canada’s first Black-owned urban radio station that Jolly launched in 2001, welcomed several celebrities during its 10-year reign. They included British business magnate Richard Branson who visited the station’s downtown office to promote his Virgin mobile smartphones.

Waiting to meet his guest, Jolly was shocked when the billionaire made his appearance.

“This guy came from his hotel by subway, he was dressed in a sweatshirt and he stopped to say ‘hello’ to staff members before settling in to do what he came for,” he recounted. “He then left with a friendly smile and wave. There was no limousine circling the block waiting for him and no security at his side.”

While very impressed by his style, Jolly wasn’t totally surprised by Branson’s humility.

“I met his parents on a farm in northeast South Africa near the border with Mozambique and they are humble and ordinary people,” he said. “Richard’s mother said he called them at least four times daily from wherever he is to see how they are doing.”

When husband and wife Jay Z and Beyoncé visited the Flow studio, they brought along about 10 security personnel.

“Hours before their arrival, security came to check out the studio and make demands,” said Jolly.

Kanye West’s bizarre behaviour is still etched in his memory.

When told he could not refer to women as ‘bitches’ on the air, the award-winning hip hop artist stormed out of the interview.

“He has been successful and God bless him, but he has issues,” said Jolly. “I hope he gets help.”

These stories along with Jolly’s life as a civil rights activist, educator, entrepreneur, newspaper publisher and broadcaster are recorded in his autobiography, ‘In the Black: My Life’ that was launched last Saturday night at Miss Lou’s Room at Harbourfront Centre.

Jolly has had a hand in the establishment of several business and community organizations in the Greater Toronto, but starting Canada’s first Black commercial radio station after two failed attempts takes pride of place among his outstanding accomplishments.

With the industry becoming more competitive and major radio stations dramatically increasing their economies of scale, FLOW – as a stand-alone station -- was backed into a corner.

CTV assumed ownership of the station in February 2011.

During its tenure, many in the Black community felt that FLOW backtracked from its promise to deliver a ‘modern-day reflection of the rich musical traditions of Black musicians and Black-influenced music over at least the past century’ with a broader mix of reggae, soca, jazz and R & B.

Jolly, however, defended the station’s decision to play a Canadian mixture of music that appealed to mainly young people.

“I don’t think there is anything I could have done differently and time has proven me correct,” he said. “We were highly criticized for not playing a lot of reggae music, but the market conditions determined what we played.”

FLOW helped launch the careers of many local artists and provided a gateway to young professionals to enter the radio and television industry.

“When we started, there wasn’t anything like a Black music or program director,” he pointed out. “Many artists, including Drake whose music we were the first station to play, cut their teeth at FLOW, Black kids were allowed to bring in their music on Tuesday’s for an opportunity to be aired. We gave out about $4 million to help promote Black music in Canada and the station brought great awareness to the city and was a training ground for a lot of young people. I am happy about that. There were very few Blacks in radio, especially in positions of power, before FLOW emerged.”

Over the years, Jolly has marched with protestors demanding social justice and contributed significant sums of money to community organizations and causes.

He said his passion for social activism and philanthropy comes from his parents.

“They always stood up for other people and helped out in any way they could,” Jolly, who co-founded the Black Action Defence Committee (BADC) in 1988 in the aftermath of the police shooting of Lester Donaldson, said. “My mother was a Justice of the Peace and she was known in the community as the only one the police could go to after midnight if they thought someone really deserved bail. I remember there was one instance where there was a young lady in our community with several children who was incarcerated. My mother went down to the court house and successfully pleaded with the judge to release her.

“If you didn’t have food, you were welcomed to our home. At my mom’s funeral, I learnt she took in almost 25 disadvantaged children into her home. She always helped people. We had the only well in our district and there was always a procession of people lining up to get water. I was raised by a giving family.”

A graduate of Cornwall College which honoured him with a ‘Man of Might” award two years ago, Jolly – who financially supports Industry Cove basic school that his late mother founded -- came to Canada in 1955 to pursue post-secondary education.

He completed a Bachelor of Science degree in Agriculture at McGill University and was a nutrition researcher for the Jamaican government for two years before returning to Canada in 1962 to work as an air pollution researcher, high school chemistry and science teacher and owner the defunct Contrast newspaper and nursing homes in the Greater Toronto Area.

Cognizant of the influence that entrepreneurs can wield, Jolly conceived the idea for a black business organization.

“The time has come for us to assert ourselves in this society,” he wrote in a letter sent to friends. “We have among us ‘blushing unseen’ some of the greatest minds in the world. These abilities and potentials must now be realised in the fullest, for our sake and four our children’s sake.”

The Black Business & Professional Association (BBPA) was launched in 1983. Its signature event is the Harry Jerome Awards that honours excellence in Canada’s Black community.

Jolly didn’t hide his dissatisfaction with the direction of the organization in the last few years.

“I believe they have lost their way somewhat in a political sense as they are often used for the self-promotion of the leadership rather than as a service to the community,” he pointed out. “…At the first event, we gave accolades to achievers and we used achievers to make the presentations so that we could say to those who doubted that excellence pervades in the Black community that our kids are getting straight A’s in high school and will be rewarded and look at who is make the presentation. We wanted to make the point that not all Blacks are on welfare. The idea was for those attending the event to leave with a sense of pride and fulfillment.”

Seated at the back of the banquet hall for the organization’s 30th anniversary in 2012, Jolly walked out and has never attended another awards ceremony.

“That was it for me,” the former Toronto International Film Festival director said.

Published by ECW Press, Jolly dedicated the book to his only grandchild, three-year-old Elias Jolly Klym.

“He’s of mixed race and it would be good for him to know what happened on the Black side of his family,” said 81-year-old Jolly who is a Caribbean Tales board director. “He might have some things to be proud of and it would be good for his children too.”