Walters’ new book tells the Jamaican story

Calling it a masterpiece and significant literary and historical body of work that all Jamaicans should be proud of, University of Toronto professor emeritus Dr. Keith Ellis hopes that Ottawa resident Ewart Walters’ new book, We Come from Jamaica: The National Movement 1937-1962, will be published in Spanish.

The renowned scholar, translator and Latin American literature critic is confident the book will appeal to the public in Spanish-speaking countries, particularly Cuba and Venezuela who, he said, relish books and are voracious readers.

“This is the book of an outstanding essayist,” said Ellis who was the first Jamaican-born scholar to be awarded an honourary doctorate by the University of Havana and the first Black to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada which is the highest honour a scholar can receive in the arts, humanities and science. “There is the literary art that he’s aware of and that he has practiced to perfection in the book. It’s that literary art that draws readers to the content.

“We also find him zooming in an out and capturing the ubiquitous and constant movement, the vibrancy of the country and the people he portrays. He has found this fitting technique which is itself a symbol because of what comes through as his real motivation for writing this book and that is his enduring respect, his love and wanting the best for the Jamaican people.”

The publication charts the course of the national movement, a period and group of people who were instrumental in propelling Jamaica out of slavery and ‘apprenticeship’ to nationhood and independence.

The Toronto book launch took place last week.

“This was a period when people were really serious about taking on the task of doing for themselves what the colonial masters didn’t do, didn’t allow us to do or didn’t give us an opportunity to do,” said Ellis who graduated from Calabar High School and taught Spanish and History for three years before migrating to Canada and lecturing in Latin American Literature and Culture at the U of T for 37 years. “It was a very challenging era and it was good to see Jamaicans in one way or another taking up the challenge.”

Writing is an obsession for Walters.

After spending a year with The Public Opinion that folded in 1962, the Jamaica Gleaner and the Jamaica Daily News with which he worked from its inception in 1973 to 1976 (the publication ceased in 1983), Walters started The Spectrum monthly newspaper in August 1984 after leaving the Jamaica Foreign Service, having served five years as counsellor in Ottawa and a year as consul in New York.

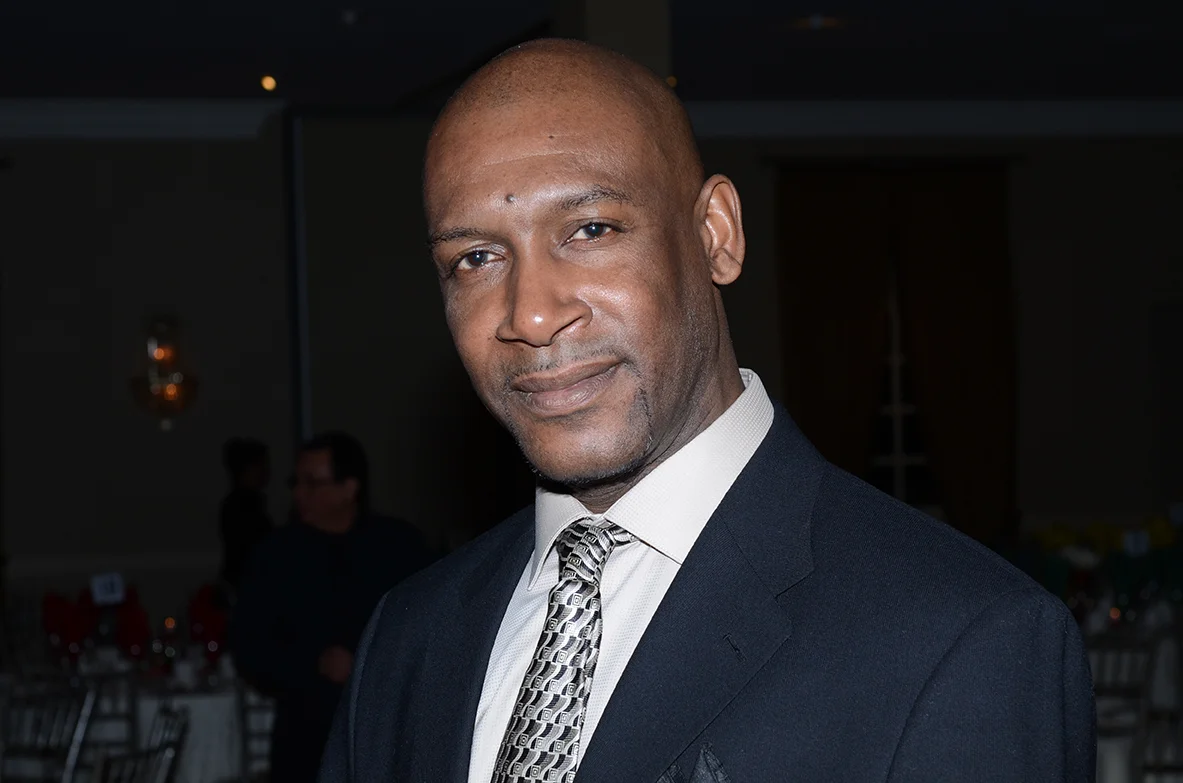

Ewart Walters (r) presents a copy of his new book to Jamaica's consul general George Ramocan

The first Black editor of Carleton University’s weekly student newspaper, Walters said the book’s title was taken from a speech that the late Norman Manley presented on several occasions.

“What he was doing was projecting a time when all of the people who had come out of the bond of slavery and were left destitute had to get together and look after themselves and, in the process, form a nation,” he pointed out. “He was saying to them that we want to build this country into a place of substance and when it happens, you will be proud to tell people that we come from Jamaica.”

The book pays tribute to several Jamaicans who aren’t prominent household names.

They include Amy Bailey who campaigned for the right of every Jamaican to be employed in stores and offices and fought relentlessly for women’s liberation before she died in 1980 at age 95; University College of the West Indies co-founder Sir Philip Sherlock and his brother Hugh Sherlock who penned the words of the Jamaican national anthem and created Boys Town, one of the most effective inner city institutions, and Osmond Theodore (OT) Fairclough who, with Englishman Headley Jacobs, co-founded The Public Opinion in 1937.

Born in Westmoreland in 1904, Fairclough went to Haiti in the 1920s and was employed with the National Bank of Haiti for eight years up until 1932, rising from credit clerk to assistant manager. On his return to Jamaica, he was unable to secure a banking job because of his skin colour.

“He started a newspaper to promulgate his ideas about nationhood,” said Walters who retired from the federal public service four years ago. “After that, he created the People’s National Party as part of the national movement and then got Norman Manley to become the party leader. I worked with OT for a year at The Public Opinion and didn’t know that.”

Other speakers at the launch included Rachel Manley, the daughter of late Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley.

“Ewart is a journalist and not a word is wasted,” said Manley who won the Governor General’s Award for English Language non-fiction in 1997 for her memoir, Drumblair: Memories of a Jamaican Childhood. “He has been able to cover these years richly and deeply and yet in a journalist’s economic language with straightforward simplicity and in a clear accessible form, for Ewart’s structure is not only chronological as a story, but also separates into cameos featuring pivotal heroes and heroines, movements and themes and religions which makes it a user-friendly reference book.

“If every school child in Jamaica left high school with this overview of those 25 years and its pertinent themes behind them in their heads, what a difference it would make to the landscape of background information that would frame their Jamaican consciousness. I am hoping high schools in Jamaica will offer this to students in their history classes and that these books will find their way into Canadian schools as well. Nowhere will they have a better catalogue of events with a fairer proposal of questions they can discuss and ponder through the years as they come to know their young country’s story.”

Jamaica achieved its independence on August 6, 1962.